Antarctica

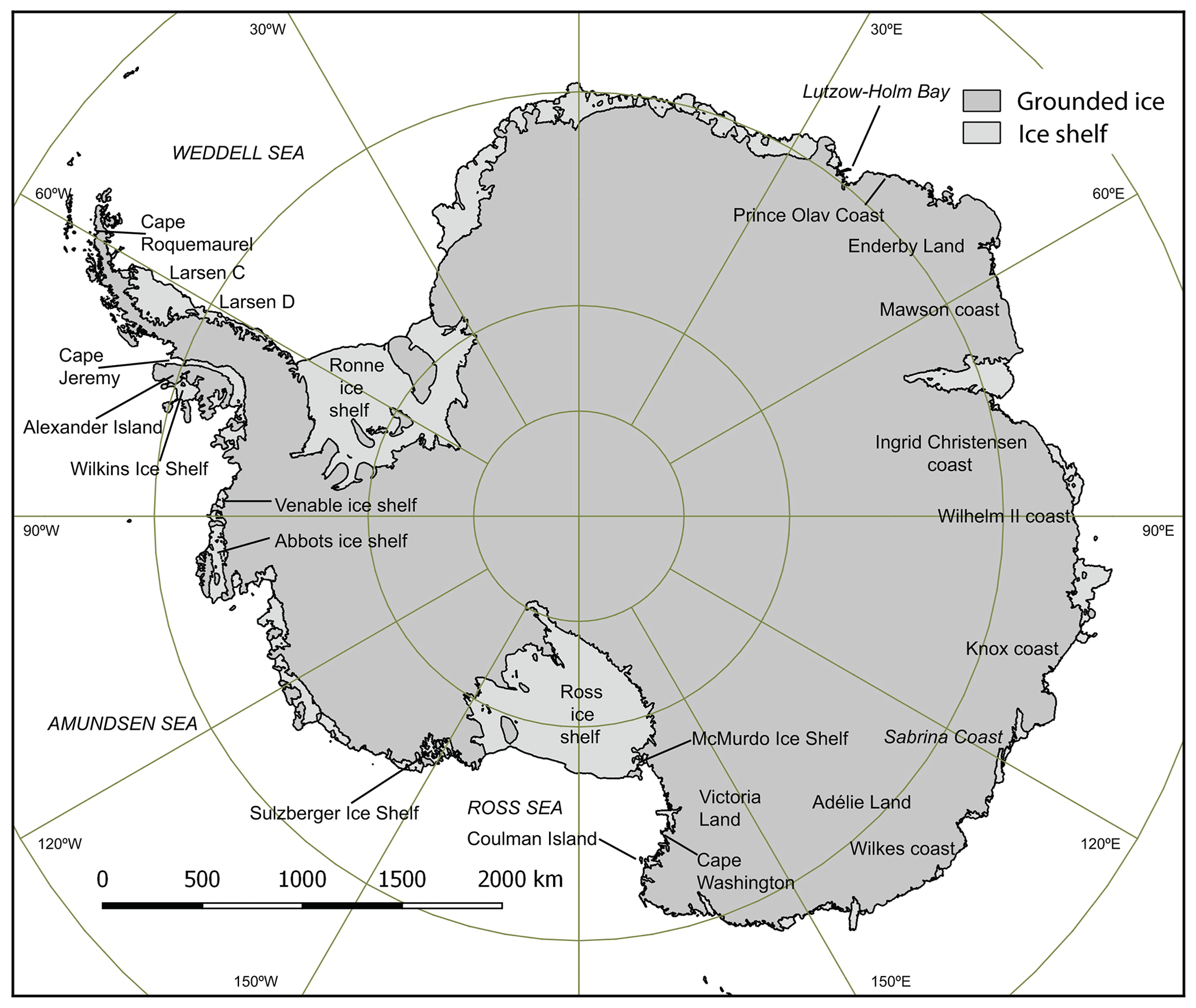

The Antarctic is a continent in the earth's southern hemisphere. Most parts of the continent is inside the Antarctic Circle (66.33o S) and the south pole is located near its center (the Antarctic Circle is shown in the map below as a dashed circle with the number "66.33" near the Antarctica peninsula). It is surrounded by the Southern (or Antarctic) Ocean which connects to the southern Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. It has an area of more than 14 million km2. Below is a map of the Antarctica showing its location among other continents:

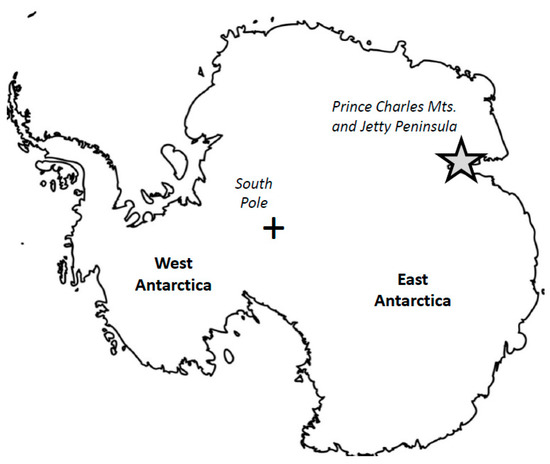

Some 98% of Antarctica is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, the world's largest ice sheet and also its largest reservoir of fresh water. Averaging at least 1.6 km thick, the ice is so massive that it has depressed the continental bedrock in some areas more than 2.5 km below sea level. The present Antarctic ice sheet accounts for 90 percent of Earth's total ice volume and 70 percent of its fresh water. It houses enough water to raise global sea level by 200 ft. if melted. Below are: (1) satellite image of Antarctica and (2) a more detailed map of Antarctica:

Antarctica’s ice sheet has been formed by snow. The snow has accumulated over hundreds of thousands of years and compressed into ice. The ice generally flows from the center of the continent towards the surrounding ocean forming thousands of glaciers extending into the sea. Great pieces of ice break away at the coast and drift away as icebergs. Beneath the ice sheet is a hidden landscape of mountains, valleys and plains. Only about 1% of the continent’s rock base is visible. Below is a satellite image showing some of the visible tall mountains and glaciers:

Antarctica is a remote area and very few people had the chance to visit it, even today. Surprisingly, ancient people had already speculated the existence of Antarctica. Some ancient Greek astronomers believed that the earth is a sphere and there are north an south polar regions. A Greek astronomer during the time of the Romans, Claudius Ptolemy, published a book, named Geographia, round 150 CE and speculated the existence of “Terra Australis Incognita” (in Latin, “Terra Australis” means “Southern Land” and Incognita means unknown). Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that continental land in the Northern Hemisphere should be balanced by land in the Southern Hemisphere. The Romans already knew the existence of the Indian Ocean. Ptolemy believed that the Indian Ocean was enclosed on the south by land and speculated a Terra Australis Incognita.

After Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas around 1492, Europeans started to explore areas around South America. In 1525 Spanish navigator Francisco de Hoces discovered an area of sea at the tip of South America. Later, people determined that this is the shortest sea passage between Antarctic and South America. This sea passage is called Mar de Hoces passage in Spanish publications and the Drake passage in English language publications (named after and Englishman Francis Drake). Before the Panama Canal was operational, ships used this passage to go between Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Below is a map of the Drake passage:

As the Drake passage is the narrowest passage between Antarctica and another landmass (about 800 km wide, or 500 miles), its existence and shape strongly influence the circulation of water around Antarctica and the global oceanic circulation, as well as the global climate. The Drake Passage is considered one of the most treacherous voyages for ships to make. Ocean currents meet no resistance from any landmass, and waves top 40 feet (12 m), hence its reputation as "the most powerful convergence of seas".

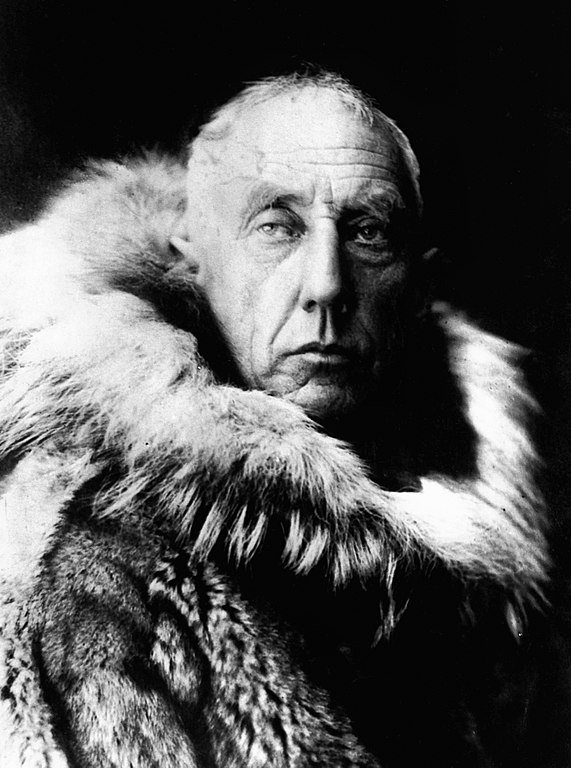

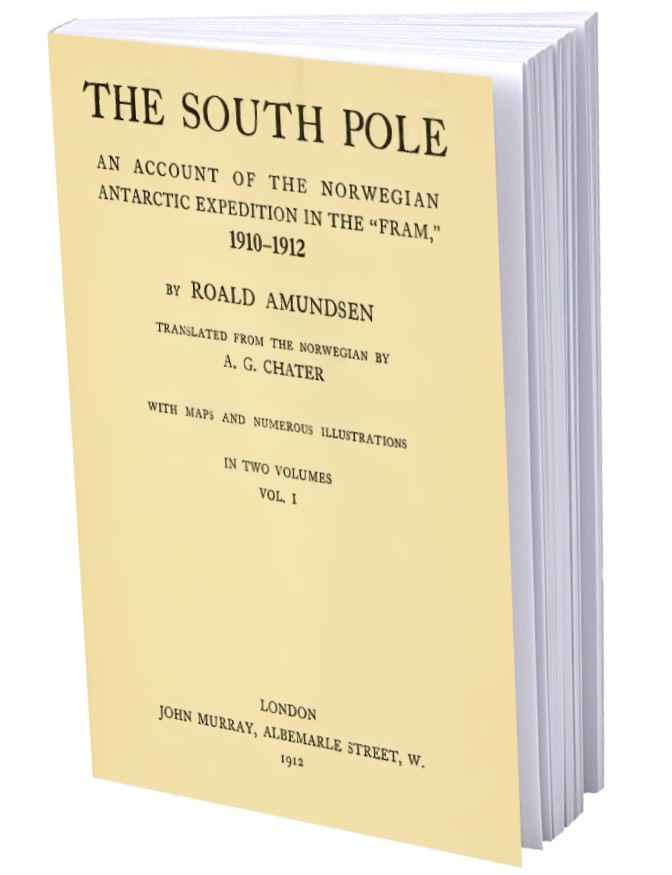

After the Drake passage was discovered, Europeans continue to sail south. In the 17th century several expeditions were organized to explore the area. Captain John Davis, an English-born American sailor, recorded on his ship Cecilia’s logbook that his crew had landed at Hughes Bay (64o 01’ S) on Feb. 7, 1821 (Hughes Bay is a bay on the northwest tip of the Antarctic Peninsula ). However, his claim was not confirmed. The first undisputed landing on Antarctica did not occur for another 74 years, on 24 January 1895, when a group of men from the Norwegian ship Antarctic went ashore to collect geological specimens at Cape Adare. The first team who reached the South Pole on December 14, 1911 was lead by Roald Amundsen. He wrote a book about his expedition, and his book is available below. This is a portrait of Amundsen:

As more specimens and fossil records were collected from Antarctica, people got a better understanding of the continent. Antarctica’s fossil records show that it was not always the icy continent we know today. Antarctica once had abundant plant and animal life, including dinosaurs. Forests once stretched from Australia through Antarctica to South America, all three of which are remnants of the ancient Southern Hemisphere supercontinent called Gondwana. Gondwana was a large landmass formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) that included South America, Africa, Arabia, Indian subcontinent, Antarctica and Australia. It began to break up during the Jurassic (about 180 million years ago). The final stages of breakup involving the separation of Antarctica from South America (forming the Drake Passage) and Australia. Below are: (1) Glossopteris (fossil) leaf of Permian age found at Prince Charles Mountains, and (2) location of Prince Charles Mountains:

Today, the wildlife of Antarctica need to adapt to the dryness, low temperatures, and high exposure common in Antarctica. The interior of the continent has extreme weather. But there are relatively mild conditions on the Antarctic peninsula and the sub-Antarctic islands, which have warmer temperatures and more liquid water. Much of the ocean around the mainland is covered by sea ice. The oceans themselves are a more stable environment for life, both in the water column and on the seabed.

There is relatively little diversity in Antarctica compared to much of the rest of the world. Terrestrial life is concentrated in areas near the coast. Flying birds nest on the milder shores of the Peninsula and the sub-Antarctic islands. Eight species of penguins inhabit Antarctica and its offshore islands.

Over 1,000 fungi species have been found on and around Antarctica. Larger species are restricted to the sub-Antarctic islands, and the majority of species discovered have been terrestrial. Plants are similarly restricted mostly to the sub-Antarctic islands and the western edge of the Peninsula. Some mosses and lichens however can be found even in the dry interior. Many algae are found around Antarctica, especially phytoplankton, which form the basis of many of Antarctica's food webs.

Human activity has caused introduced species to gain a foothold in the area, threatening the native wildlife. A history of overfishing and hunting has left many species with greatly reduced numbers. Pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change pose great risks to the environment.

There are a few types of animals that have subspecies living mainly in Antarctica and sub-Antarctic areas. We look at two of them: penguins and seals.

(1) Penguins

Penguins are a group of aquatic birds that do not fly. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. They are highly adapted for life in the water and have flippers for swimming. Most penguins feed on krill, fish, squid and other forms of sea life which they catch with their bills and swallow it whole while swimming. A penguin has a spiny tongue and powerful jaws to grip slippery prey. Today, larger penguins generally inhabit colder regions, and smaller penguins inhabit regions with temperate or tropical climates.

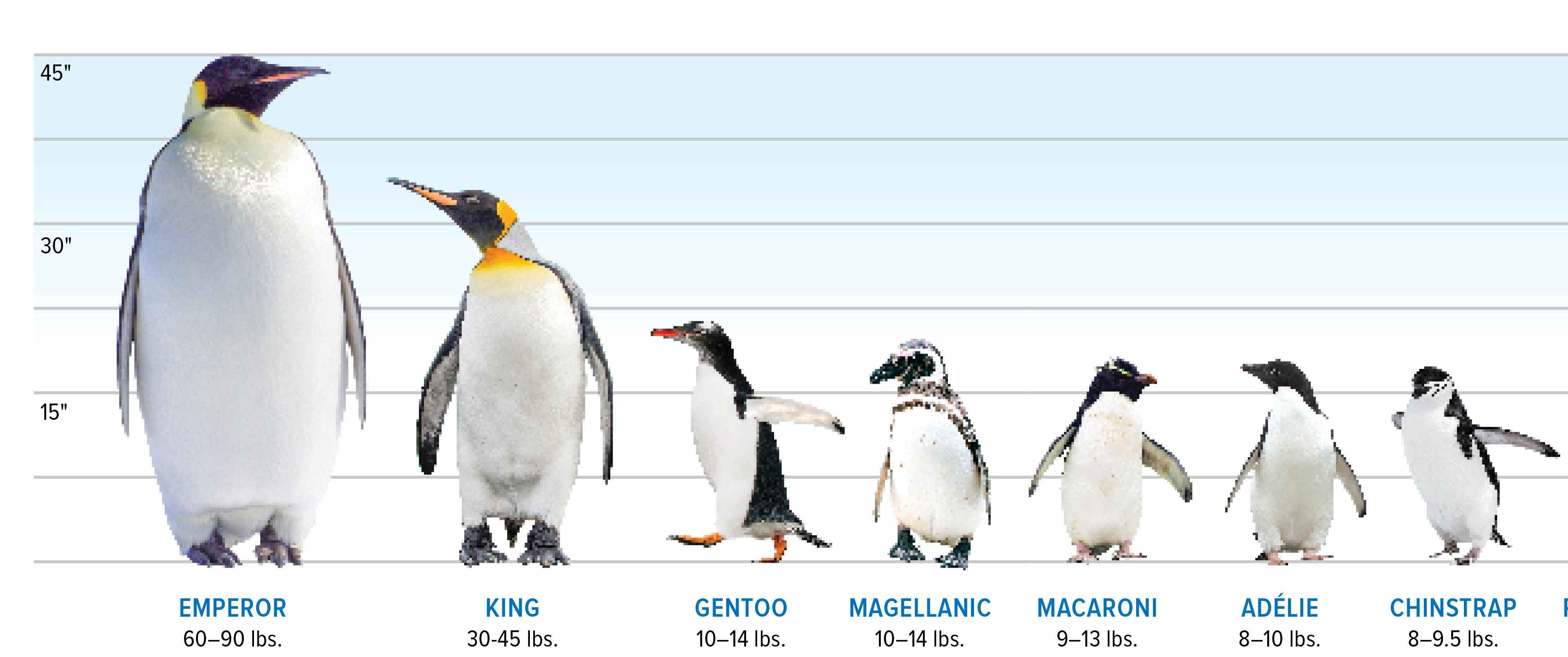

The largest living species is the Emperor penguin. On average, adults are about 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) tall and weigh 35 kg (77 lb). The smallest penguin species is the little blue penguin, also known as the fairy penguin, which stands around 33 cm (13 in) tall and weighs 1 kg (2.2 lb). Below is an illustration showing different types of penguins (note: Magellanic penguins do not live or breed in Antarctica):

The emperor penguin is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. Like all penguins emperor penguins have streamlined bodies to minimize drag while swimming, and wings that are more like stiff, flat flippers. Its diet consists primarily of fish, but also includes crustaceans, such as krill, and cephalopods, such as squid. The tongue is equipped with rear-facing barbs to prevent prey from escaping when caught. While hunting, the species can remain submerged around 20 minutes, diving to a depth of 535 m (1,755 ft). It has several adaptations to facilitate the deep dive, including an unusually structured to allow it to function at low oxygen levels and the ability to reduce its metabolism and shut down non-essential organ functions.

The only penguin species that breeds during the Antarctic winter, emperor penguins trek 50–120 km (31–75 miles) over the ice to breeding colonies which can contain up to several thousand individuals. The female lays a single egg, which is incubated for just over two months by the male while the female returns to the sea to feed. Parents subsequently take turns foraging at sea and caring for their chick in the colony. The lifespan is typically 20 years in the wild, although observations suggest that some individuals may live to 50 years of age. Below is a picture of emperor penguins:

Emperor penguins have no fixed nest sites that individuals can use to locate their own partner or chick, emperor penguins rely on vocal calls alone for identification. They use a complex set of calls that are critical to individual recognition between parents, offspring and mates. Chicks use a frequency-modulated whistle to beg for food and to contact parents.

The king penguin is the second largest species of penguin, smaller, but somewhat similar in appearance to the emperor penguin. King penguins mainly eat lanternfish, squid and krill. On foraging trips, king penguins repeatedly dive to over 100 meters (300 ft), and have been recorded at depths greater than 300 meters (1,000 ft). Predators of the king penguin include giant petrels, skuas, the snowy sheathbill, the leopard seal and the orca. King penguins breed on sub-Antarctic islands between 45 and 55°S, at the northern reaches of Antarctica, as well as Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands, and other temperate islands of the region. Below are (1) a picture of a king penguin and a chick, and (2) closeup of the head of a king penguin:

Gentoo penguins live about 15-20 years and are one of the fastest-swimming birds, reaching speeds up to 36 kph (22 mph). There are estimated to be about 300,000 breeding pairs of gentoo penguins in the Antarctic region, putting them second only to emperor penguins in terms of population scarcity. As adults, gentoos are the third largest penguin behind emperors and kings, reaching 50 - 90 cm (19.7 - 35.4 inches) tall and weigh 4.5 - 8.5 kg (9.9 - 18.7 pounds). They feed on a diet of squid, fish, and crustaceans. Gentoo penguins live in large, gregarious breeding colonies along the coastlines of the northern Antarctic Peninsula, South Sandwich Islands, South Shetlands, South Orkneys, and in the sub-Antarctic Falklands and South Georgia. They build nests on beaches and in grass tussocks and are highly aggressive in defending their turf. Below is a picture of gentoo penguins:

This is a link to a video of gentoo penguins (note: the link at left links to an outside website). An image extracted from the video is shown below:

This is a link to a video of a group of chinstrap penguins returning to land from the sea (note: the link at left links to an outside website). An image extracted from the video is shown below:

(2) Seals

It is easy to spot crabeater seals in Antarctica (they are also known as krill-eater seal). They live around the coast of Antarctica with only occasional sighting or stranding in the extreme southern coasts of Argentina, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.. They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 meters, or 6 feet in length; about 200 to 300 kg (450 to 650 lbs) in weight), relatively slender and pale-colored. There is little difference in size between the sexes. They spend the entire year on the pack ice zone of Antarctica, living mainly on the free-floating pack ice, which they use as a platform for resting, mating, social aggregation and accessing their prey. The pack ice zone advances and retreats seasonally, primarily staying within the continental shelf area in waters less than 600 meter deep. Below are pictures showing: (1) crabeater seal family, (2) head of a seal, and (3) their geographic distribution:

The crabeater seal are by far the most abundant seal species in the world. While population estimates are uncertain, there are at least 7 million and possibly as many as 75 million individuals. This success of this species is due to its specialized predation on the abundant Antarctic krill of the Southern Ocean (krill is a small sea animal that lives in large schools sometimes reaching density of 10,000-30,000 krills per cubic meter). Despite its name, crabeater seals do not eat crabs. Below is a picture of a krill:

Of all the Antarctic seal species, crabeater seals are the most sociable. Younger seals gather in groups on the pack ice, sometimes with as many as 1,000 individuals. When it’s time to hunt, groups of hundreds of seals will dive together. Their behavior changes with time. Older seals prefer to hunt alone or in small groups of just three or four individuals. This is a video of a group of seals on a floating pack ice (note: the link at left links to an outside website). An image extracted from the video is shown below:

Crabeater seals are reproduced in Antarctica in the ice. Like most seals, they breed during the first months of spring from October to December. They reach sexual maturity between 3-4 years old. Females are more successful with childbirth after 5 years of age. Unlike many other seals that give birth in colonies, crabeater seals go to the ice to give birth alone. Then, the male protects the female and the puppy. At birth, crabeater seals weigh approximately 44 pounds (20kg) and grow more than five times in size to 240 pounds (110kg). Females fast during the lactation period, losing up to 50 percent of their body weight. In turn, males also lose a significant proportion of their weight, when they help their partners and their offspring, and protect them from other surrounding rivals.

Most crabeater seals live for 20 to 25 years, although some are known to live up to 40 years in the wild.

One of the predators of crabeater seals is the leopard seal. First-year mortality of crabeater seals is exceedingly high, possibly reaching 80%, and up to 78% of crabeaters that survive through their first year have injuries and scars from leopard seal attacks. The leopard seal, also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey including other seals, octopus, krill, birds, fish and penguins. Leopard seals are pagophilic ("ice-loving") seals, which primarily inhabit the Antarctic pack ice between 50˚S and 80˚S, although some can be seen in other continents near Antarctica. Most leopard seals remain within the pack ice throughout the year and remain solitary during most of their lives with the exception of a mother and her newborn pup. Below is a picture of a leopard seal:

A book on South Pole expedition:

A first-hand account of an Antarctica expedition by Roald Amundsen (1872 - 1928). Sailed on the ship "Fram," he and his teammates were the first to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911 and planted a Norwegian flag there. This is the book:

"The South Pole: An Account Of The Norwegian Antarctic Expedition In The "Fram" (1910-12)"

Volume One (file size: about 25 MB)

Volume Two (file size: about 26 MB)

Books and paper on the geography of Antarctica:

(1) Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World - A N T A R C T I C A (United States Geological Survey) (file size: about 19 MB)

(2) Exploring the Antarctic (Indian Space Research Organization) (file size: about 30 MB)

(3) The Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica

Model (note: the model is a 4MB JPEG file)

Papers on Drake passage:

(2) Glacial reduction and millennial-scale variations in Drake Passage throughflow

Paper on fossil records:

The fossil record of Antarctic land mammals: commented review and hypotheses for future research

Papers on emperor penguins:

(1) Protecting Emperor Penguins: Fact Sheet

(2) Emperor penguin body surfaces cool below air temperature

(3) Emperor Penguins Breeding on Iceshelves

Papers on king penguin:

(1) Body surface rewarming in fully and partially hypothermic king penguins

(2) Using Predicted Patterns of 3D Prey Distribution to Map King Penguin Foraging Habitat

Paper on Adelie Penguin:

Papers on seals:

A report:

Antarctica: Overview of Geopolitical and Environmental Issues (Congressional Research Service)