Egyptian Writing

People in Egypt had developed one of the earliest written language dated back to around 3400 BCE. It is also the longest-attested human language, with a written record spanning over 4,000 years. Over the long period of Egyptian history, four different writing scripts had been developed: Hieroglyphs, Hieratic, Demotic, and Coptic. These scripts did not all appear simultaneously, but appeared consecutively over the long period that the ancient Egyptian language existed. It also shows the progression in thinking of the ancient Egyptians who knew that the complexity and development of life would require the invention of suitable means of communication to improve and record the wider and more developed activities.

Hieroglyphic script was the first script used by the ancient Egyptians to write their language. The term is derived from two Greek words and they mean “sacred inscriptions.” It is a beautifully written pictorial script which required special material and special people to write it. Hieroglyphic writing was used mainly for inscription on the walls of sacred places such as temple walls, monuments, and tombs. They began to go out of use in the Middle Kingdom and after 500 BCE were occasionally used. As described further down on this page, the discovery of the Rosetta Stone allowed the deciphering of hieroglyphic script. Today, we are able to read old documents written in this script and even write them. In fact, Egyptian hieroglyphs has been added to the Unicode Standard and is available as "Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyphs" font from Google. Below is hieroglyphs from the tomb of Seti I, a king during the New Kingdom period:

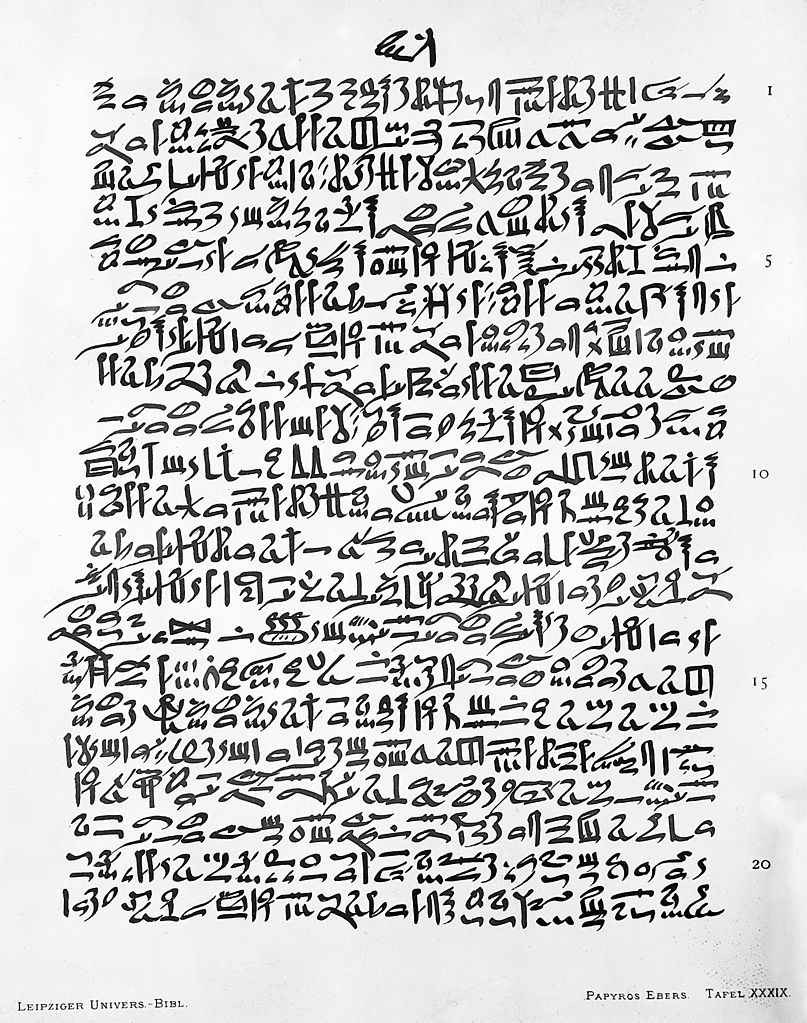

As Egypt developed, Egyptians needed to invent a different and simplified script to suit their overgrowing society and to fulfill administrative needs. Hence they invented a cursive script known as Hieratic. The word “hieratic” derived from a Greek word meaning “priestly,” and it was called "priestly" because this script was the usual writing used by priests. The name is now been given to all the earlier styles of script that are cursive enough for the pictorial forms of the original hieroglyphic signs to be no longer recognizable. It was written mainly on papyrus and ostraca, however, occasional hieratic inscriptions also appear on stone. Below is a page from the Ebers Papyrus, written around 1500 B.C. using hieratic script:

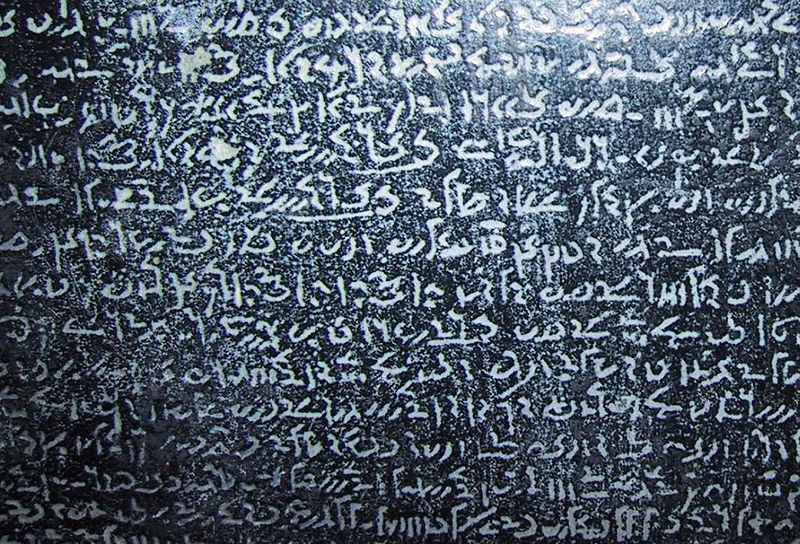

The next script is “Demotic.” The word is derived from the Greek demotikos, meaning “popular”. This script was wide use by all people. Demotic was a very rapid and simple form of Hieratic script that made its first appearance around the 8th century BCE and continued to be used until the 5th century CE. Similar to hieratic, it was written on papyrus and ostraca, and occasionally appeared on stone. Below is a replica of a portion of the Demotic script written on the Rosetta Stone:

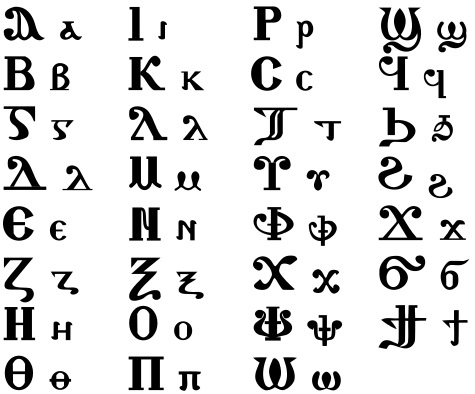

The Coptic script represents the last stage of the development of Egyptian writing. This Egyptian script was written using the Greek alphabet, in addition to seven Egyptian sign-letters borrowed from Demotic (to represent Egyptian sounds which did not appear in Greek). Writing the ancient Egyptian language with Greek letters was a political need following the Greek occupation of Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period. An important feature of this script is that it renders the vowels of the language (something which was not in Hieroglyphics, Hieratic or Demotic) and allows various highly stylized dialects to be distinguished (Sahidic, Boharic, Akhmimic, and Fayyumic). Below is a list of Coptic alphabets (uppercase and lowercase side by side):

Coptic has no native speakers today, although it remains in daily use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Alexandria and St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo, which belong to one of the six autocephalous of the Christian Oriental Orthodox Church.

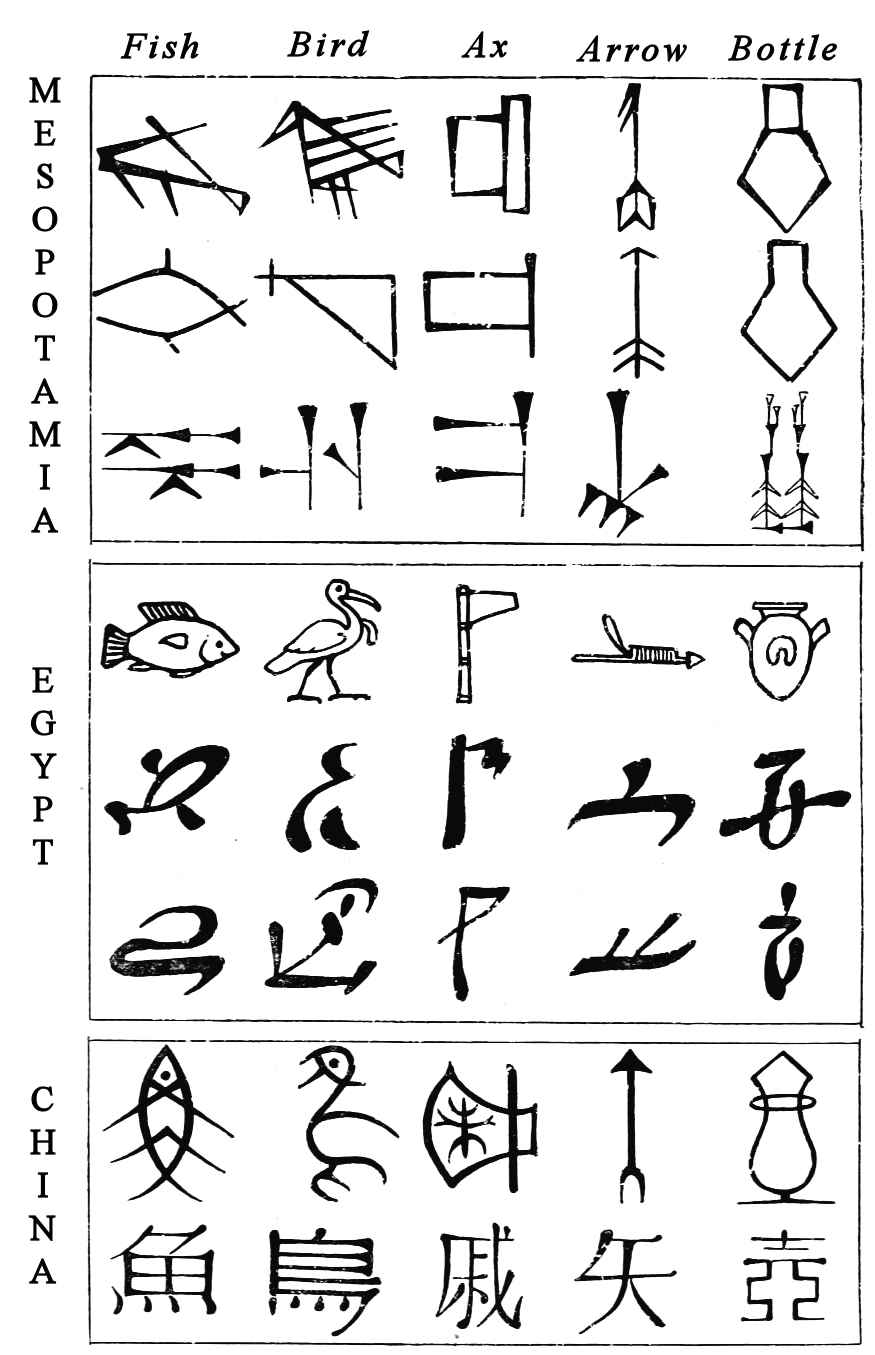

Such evolution of writing scripts is common in many cultures. Below is a comparative chart showing the evolution of Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian and Chinese characters:

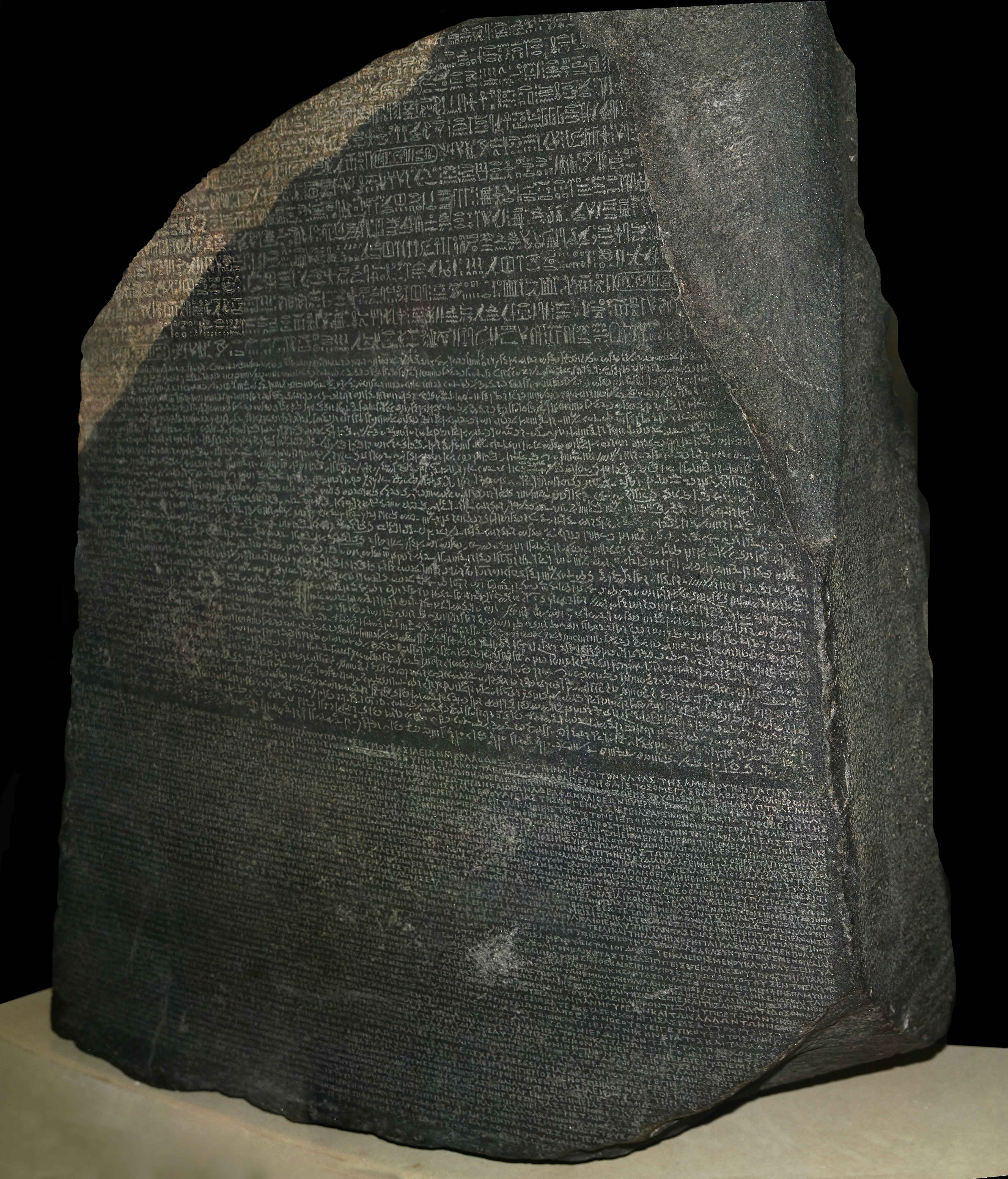

The Muslim conquest of Egypt by Arabs came with the spread of Islam and Arabic starting from the seventh century. Literary Coptic gradually declined. As a written language, Coptic completely gave way to Egyptian Arabic around the 13th century, though it may have survived in isolated places until the 16th century. Ancient Egyptian writing became unreadable until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 by French officer Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. Below is a picture of Rosetta Stone (high resolution image which can be enlarge on computer/tablet screens to read the text):

Before describing the decipherment of hieroglyphic script, let us learn a little about the script. Hieroglyphic is a pictographic-style script which was common in many ancient cultures. Egyptian hieroglyphic has about 600 symbols that might be put to three types of uses:

(1) They could be used as ideograms, as when a sign resembling a snake meant "snake."

(2) They could be used as a phonogram (or a phonetic letter similar to our alphabet), as when the pictogram of an owl represented the sign or letter “m,” because the word for owl had “m” as its principal consonant sound. It would be like us using a picture of a snake for the letter “s.” The phonograms provided a basis for the development of the alphabet (see chart below).

(3) They could be used as a determinative, an unpronounced symbol placed after an ambiguous sign to indicate its classification (e.g., an eye to indicate that the preceding word has to do with looking or seeing).

Below is a table of hieroglyphic pictogram (right column) used as phonogram, prepared by Frenchman Jean-François Champollion:

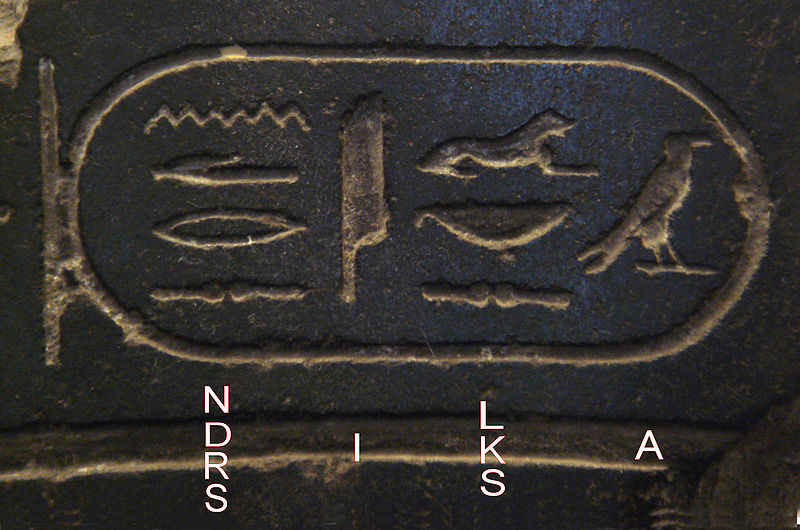

Below is Alexander the Great in hieroglyphs (the picture was taken from a display at Louvre Museum while the letters were added after the picture was taken):

One interesting characteristics of Egyptian hieroglyphic is that writing can be organized into registers of vertical columns or horizontal lines. Signs could be written from right to left, and from left to right. The signs were placed in a continuous sequence, without any punctuation marks or word spacing. Reading is according to the direction of the sign; if signs are directed towards the left, then the reading starts from left to right. If signs are directed towards the right, then the reading starts from right to left. The hieroglyphic of Alexander, shown above, indicates that it is read from right to left.

The Rosetta Stone is a stele inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BCE during the Ptolemaic dynasty. The top and middle texts are in ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts while the bottom is in ancient Greek. Demotic and Greek were already understood by people in the 19th century. However, they couldn’t read the text at the top. Several scholars had tried, without success, to unlock the code to read the pictogram at top of the stone. The decipherment of the script was finally completed by Thomas Young (1773-1829) and Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832). Young was a physician and acclaimed physicist. Champollion was a philologist (a person who studies language in oral and written historical sources).

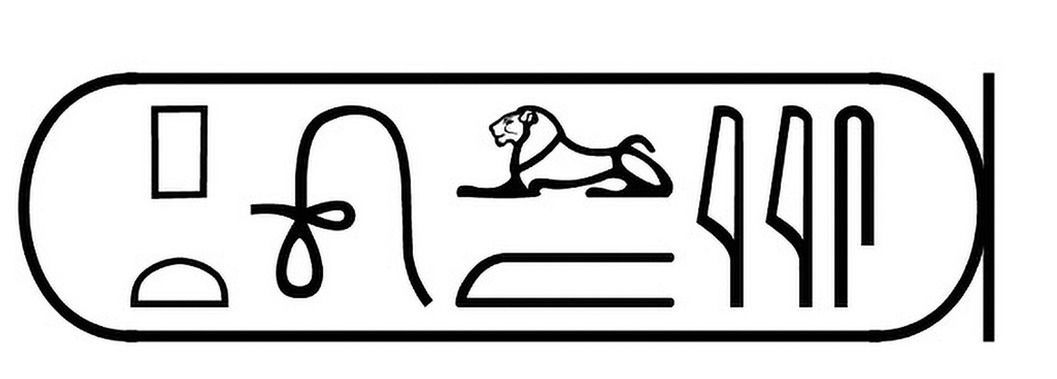

Young had been trying to decipher, out of curiosity, ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs since the French army discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799. Based on the translated Greek section of the Rosetta Stone (Young was British), Young knew the name Ptolemy should appear repeatedly throughout the hieroglyphic text. Looking at the hieroglyphs, he identified three identical "cartouches," explained below, that began the same way but had several hieroglyphs added on at the end. Through trial and error, Young concluded that the identical cartouches correspond to Ptolemy. The longer cartouches, he argued, added a title of some kind—perhaps “Ptolemy the Great.”

In Egyptian hieroglyph, royal names are put in a “cartouche,” an oval with a line at one end tangent to it. Since Ptolemy is a royal name, it was in a cartouche. Below is Ptolemy in hieroglyphics (which, based on the rules stated above, is read from left to right):

Below is the cartouche on the Stone with additional letters after Ptolemy's name (which, based on the rules stated above, is read from right to left):

But early attempts to interpret its symbols were stymied by the traditional belief that all hieroglyphics could only be translated as pictures of words. Initially Young and Champollion held to the belief that the lion (one of the symbols in the word) symbolized the word for war. In 1822 Champollion eventually worked on the idea that Ptolemy might be read phonetically. Being a philologist, he was able to reconstruct the name, sound by sound, from the Greek and Coptic into Demotic, then into an earlier hieratic script and finally into hieroglyphics. The sound he arrived at was “p-t-o-l-m-y-s” or “Ptolmis.” He presented his discovery to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Arts. A copy of his letter titled "Relative to the Alphabet of Phonetic Hieroglyphics Used by the Egyptians to Inscribe on their Monuments the Titles, Names and Sobriquets of Greek and Roman Rulers" sent to the Royal Academy can be downloaded at the end of this page.

Champollion made a second crucial breakthrough in 1824, realizing that the alphabetic signs were used not only for names of Greek and Roman rulers, but also for the Egyptian language and names. Together with his knowledge of the Coptic language, this realization allowed him to begin reading hieroglyphic inscriptions fully.

The decipherment of hieroglyphic script is important to understand ancient Egypt. Many texts inscribed on walls inside pyramids were written in hieroglyphic script and they contain important historic information of the buried persons and the society at that time. Below is a portion of a block segment from the wall of a chamber in the pyramid of Pepi I, a king of the 6th dynasty, and it is an example that hieroglyphics can be written vertically:

Below is a portion of the temple lintel of Amenemhat III, a king of the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom:

Below are publications related to Egyptian writing:

(2) The Rosetta Stone and its Decipherment

(3) Middle Egyptian - An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (file size about 13 MB)

(4) Principles of the Oldest Egyptian Writing