Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism was the dominant pre-Islamic religious tradition of the Iranian peoples. Zoroastrianism spread throughout Iranian lands into Central Asia along trade routes and further into East Asia. People in ancient empires of Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanian all practiced the faith. Below is a map of the Achaemenid Empire around 500 BCE:

It is possible that Zoroastrianism was carried by Iranian traders into China through the Silk Road as early as the sixth century BCE. Some of the earliest firm evidence of Zoroastrian presence in China is found in the "Sogdian ancient letters," dated to around 313 CE and found near Dunhuang. Indeed, ancient Chinese created a special word, 祆 , to designate this religion. Below are (1) a corner of the tomb of a believer who was buried in Xi'an China showing a person with wings and bird-like feet performing fire ceremony, and (2) the epitaph written in Chinese:

The religion survived into the 20th century in isolated areas of Iran, and is also practiced in parts of India (particularly Bombay) by descendants of Iranian immigrant known as "Parsi."

This is a symbol of Zoroastrianism:

A good description of the history of Zoroastrianism is found in the introduction section of a 2017 paper titled The Genetic Legacy of Zoroastrianism in Iran and India: Insights into Population Structure, Gene Flow, and Selection:

"Zoroastrianism developed from an ancient religion that was once shared by the ancestors of tribes that settled in Iran and northern India and is thought to have been founded by the prophet priest Zarathustra (Zoroaster in Greek). Since there is no context or documentation for the life of Zarathustra, his very existence is a matter for debate. Although some scholars have proposed that he lived in the 6th century BCE, i.e., during the Achaemenic period, most scholars now believe he lived around 1200 BCE, at a time when the ancient Iranians inhabited the areas of the Inner Asian Steppes (also a subject of great controversy) prior to the great migrations south to modern Iran, Afghanistan, Northern Iraq, and parts of Central Asia. Zoroastrianism became the state religion of three great Iranian empires: Achaemenid (559–330 BCE) founded by King Cyrus the Great and ended by the conquest of Alexander the Great, Parthian (c. 247 BCE–224 CE), and Sasanian (224–651 CE), during which time the religion as an imperial faith is best known. Zoroastrianism ceased to be the state religion of Iran after the Arab conquests (633–654 CE), although it is thought that widespread conversion to Islam did not begin until about 767 CE.

According to Parsi (i.e., Indian Zoroastrians) tradition, a group of Zoroastrians set sail from Iran to escape persecution by the Muslim majority. They landed on the coast of Gujarat (India) where they were permitted to stay and practice their religion. The date of the arrival has been the cause of speculation and varies between 785 CE and 936 CE. These dates, among others, are based on the Qisseh-ye Sanjan, a legendary account of the journey by sea from Iran and settlement in India. However, maritime trade is known to have taken place between ethnic groups from Iran, including Zoroastrians, and peoples in India long before the arrival of Islam. Down the subsequent centuries, the Indian Zoroastrians maintained contact with the Zoroastrians of Iran and later became an influential minority under British Colonial rule.

Zoroastrian communities today (2011 census) are concentrated in India (61,000 people), Southern Pakistan (1,675), and Iran—mainly in Tehran, Yazd, and Kerman—(14,000). In the last 200 years Zoroastrians, both Parsi and Irani, have formed diaspora communities in North America (14,306), Canada (6,422), Britain (5,000), Australasia (3,808), and the Middle East (2,030). Zoroastrianism is a non-proselytizing religion, with a hereditary male priesthood of uncertain origins. Among the Parsis, priestly families are distinguished from the laity. Priestly status is patrilineal, although there is also a strong matrilineal component with the daughters of priests encouraged to marry into priestly families. Remarkably, many priests preserve family genealogies that can be traced back to the purported time of arrival of Iranian Zoroastrians in India and beyond to an Iranian homeland."

As mentioned in the above paper, a large number of Zoroastrians outside of India live in North America. Below is a photo of a Zoroastrian center in Los Angeles, California with the motto "Good Thoughts, Good Words, and Good Deeds" written around the symbol of Zoroastrianism (photo taken in 2016):

Historical commentary recorded by Buddhist contemporaries of the seventh century often misinterpreted the religion (perhaps willfully) as focused upon the worship of fire. While fire is an important element in Zoroastrianism, it is not considered a deity in its own right. Rather, along with light, fire serves as an agent of purification and a symbol of the supreme deity.

This is a brief description of the belief of Zoroastrianism provided by Wikipedia (accessed 2021 and slightly modified):

"The most important texts of the religion are those contained within the Avesta, which includes as central the writings of Zoroaster known as the Gathas, poems within the Yasna that define the teachings of the Zoroaster, the main worship service of Zoroastrianism. The religious philosophy of Zoroaster divided the early Iranian gods of the Proto-Indo-Iranian tradition into ahuras and daevas, the latter of which were not considered worthy of worship. Zoroaster proclaimed that Ahura Mazda was the supreme creator, the creative and sustaining force of the universe through Asha, and that human beings are given a choice between supporting Ahura Mazda or not, making them responsible for their choices. Though Ahura Mazda has no equal contesting force, Angra Mainyu (destructive spirit/mentality), whose forces are born from Aka Manah (evil thought), is considered the main adversarial force of the religion, standing against Spenta Mainyu (creative spirit/mentality). Middle Persian literature developed Angra Mainyu further into Ahriman and advancing him to be the direct adversary to Ahura Mazda.

In Zoroastrianism, Asha (truth, cosmic order), the life force that originates from Ahura Mazda, stands in opposition to Druj (falsehood, deceit) and Ahura Mazda is considered to be all-good with no evil emanating from the deity. Ahura Mazda works in gētīg (the visible material realm) and mēnōg (the invisible spiritual and mental realm) through the seven (six when excluding Spenta Mainyu) Amesha Spentas (the direct emanations of Ahura Mazda).

In Zoroastrianism, the purpose in life is to become an ashavan (a master of Asha) and to bring happiness into the world, which contributes to the cosmic battle against evil. Zoroastrianism's core teachings include:

(1) Follow the Threefold Path of Asha: Humata, Huxta, Huvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds).

(2) Charity is a way of maintaining one's soul aligned to Asha and to spread happiness.

(3) The spiritual equality and duty of men and women alike.

(4) Being good for the sake of goodness and without the hope of reward"

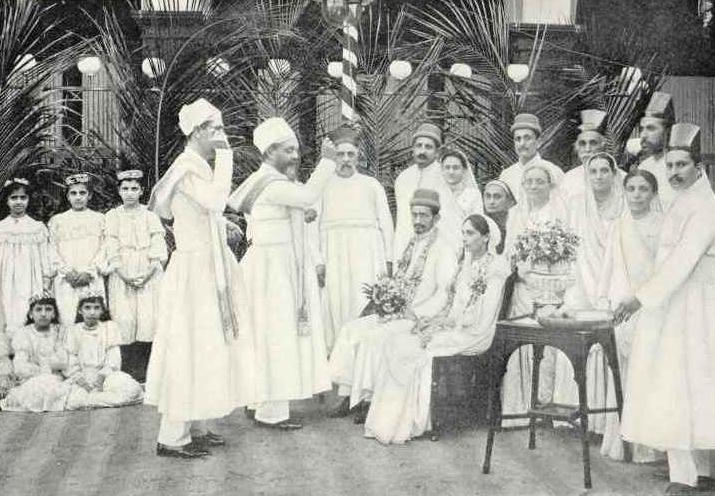

Below is a picture of a Zoroastrian wedding ceremony held in 1905:

Two books are provided below. They were both written by Professor Jackson. This is a brief bio of him at Wikipedia (accessed 2021):

"Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson, L.H.D., Ph.D., LL.D. (February 9, 1862 – August 8, 1937) was an American specialist on Indo-European languages.

He was born in New York City on February 9, 1862. He graduated from Columbia University in 1883. He was a fellow in letters there from 1883 to 1886, and an instructor in Anglo-Saxon and the Iranian languages from 1887 to 1890. After study at the University of Halle from 1887 to 1889 he became an adjunct professor of English language and literature. In 1895, he was appointed public lecturer and also appointed to the newly founded professorship of Indo-Iranian languages at Columbia University, where he remained until 1935.

He was well known as a lecturer on English literature and the Orient. In 1901, during a visit to India and Ceylon, he received special attention from the Parsees, who presented to Columbia a valuable collection of Zoroastrian manuscripts in recognition of the instruction there given by him in their ancient texts. In 1903 he made a second journey to the Orient, this time visiting Iran. He also visited Central Asia sometime before 1918.

Jackson's grammar of Avestan, the language used in the Zoroastrian scriptures, is still considered to be the seminal work on the topic. Jackson was one of the directors of the American Oriental Society.

He died on August 8, 1937."

Zoroaster, the Prophet of Ancient Iran

The following is information about Zoroastrianism's religious text, the Avesta, provided by Wikipedia (accessed 2021):

"The Avesta (/əˈvɛstə/) is the primary collection of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, composed in Avestan language.

The Avesta texts fall into several different categories, arranged either by dialect, or by usage. The principal text in the liturgical group is the Yasna, which takes its name from the Yasna ceremony, Zoroastrianism's primary act of worship, and at which the Yasna text is recited. The most important portion of the Yasna texts are the five Gathas, consisting of seventeen hymns attributed to Zoroaster himself. These hymns, together with five other short Old Avestan texts that are also part of the Yasna, are in the Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan language. The remainder of the Yasna's texts are in Younger Avestan, which is not only from a later stage of the language, but also from a different geographic region."

Avesta, The Bible of Zoroaster