West Nomads (Antiquity to Mongol Empire)

The first group of nomadic people that had substantial interaction with the sedentary societies at the west was the Scythians. They were ancient nomadic people between 7th century BCE and 2nd century CE. They once dominated the western portion of the Eurasian Steppe. They fought with ancient powers such as the Neo-Assyrian empire (911-609 BCE) and Achaemenid empire (550-330 BCE) and outlasted them. After 2nd century CE they were absorbed by a rival nomadic tribe. Below is a map showing the maximum reach of Scythia (words in black are present-day names of various areas surrounding the Scythians).

We don’t know much about the origins of the Scythians. Many historians believe that they were Iranian origin and spoke a language belonged to a eastern branch of the Iranian language. Recently there are genetic studies of the Scythians but no solid conclusion. The Scythians originated in Central Asia and they arrived the Caucasian Steppe probably in the 8th centuries BCE as part of the significant movement of the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe. From their base in the Caucasian Steppe, the Scythians conquered the Pontic Steppe to the north of the Black Sea (corresponding to parts of modern-day Ukraine, southwest Russia, Kazakhstan). They settled there in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Below is a present-day map showing the locations of the above-mentioned countries:

The Scythians founded a rich, powerful empire centered on what is now Crimea, Ukraine. The empire survived for several centuries before succumbing to the Sarmatians (another Steppe tribe) during the period from the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Below is a picture of the remains of a Scythian settlement in Crimea:

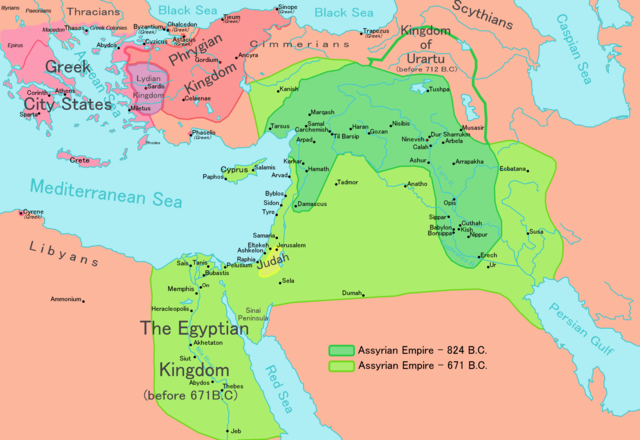

The first major empire that did battles with the Scythians were the Neo-Assyrian empire of the Mesopotamia (approximately present-day Iraq). The first mention of the Scythians in the records of the Neo-Assyrian empire was around 680 BCE. The battles lasted for decades. There was no clear winner, but the battles were one of the reasons for the weakening of the Neo-Assyrian empire. Eventually the Babylonians overthrew the Neo-Assyrian empire in 609 BCE. Below is a map showing the locations of the Scythians (top right) and the Neo-Assyrian empire (in green):

On the Persian plateau there was a great king, Cyrus the Great. He conquered many neighboring countries, including Babylon, and found the Achaemenid empire (550-330 BCE). His grandson, Darius the Great (reign: 522-486 BCE), continued to expand the empire and ruled the empire at its territorial peak.

Scythia’s most spectacular victory was perhaps the battle against the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Around 500 BCE Darius led a major war against the Scythians by attacking Scythia with a force of around 700,000 soldiers. The Scythians fought the Persians using a strategy of attrition: leading the enemy deep into friendly territory, stretching their supply lines, then, with hit-and-run and ambush tactics, finishing their opponent off with arrows shot from horseback. The attack was repelled and the Persians retreated back to Persia. The war gave the Scythians a reputation of being invincible. Below is a map of the relative locations of the Scythians and the Persian Achaemenid empire:

Armed with the success, the Scythians expanded into the present-day Bulgaria all the way to the Danube river. They often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids, and Scythian incursions reached the Hungarian Plain.

The Scythians had better relationship with the Greeks. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who lived around 430 BCE and visited Scythia, was the major source of our information about the Scythians. Some royal families of Scythia intermarried with Greek royals about the time of Herodotus. Many Scythians were Hellenized.

The Scythians controlled an important part of the Silk Road, a vast trade network connecting Europe, Persia, India and China. As the Scythians became rich, they developed their style of artwork. In the earlier period Scythian art included very vigorously modeled and stylized animal figures, shown singly or in combat. As the Scythians came in contact with the Greeks at the Western end of their territories, their artwork influenced Greek art, and was influenced by it. Below are pictures of (1) a Scythian comb, (2) a neckpiece, and (3) a vessel. More than 60 photos of Scythian art collected at different museums are shown after page 208 of the book, The Schythians, which is available near the end of this webpage.

One characteristics of the Scythian society was the eminent role women played in the military and political life of the society. For example, the warrior class was an important social caste in the Scythian society, and documentary and archaeological evidence showed that significant number of Scythian women belonged to the warrior class.

Starting from around 500 BCE, another tribe from the Eurasian Steppe called the Sarmatians (Latin: Sarmatae) fought with the Scythians. The Greek historian Herodotus called them the Sauromatae and said that they were the descendants of Scythian fathers and mothers of another tribe. The Sarmatians were likely a federation of several tribes and many of them were disgruntle groups of Scythians. This led Herodotus to mistaken the origins of the Sarmatians.

After long battles between the Scythians and Sarmatians, by 200 BCE the Scythians could only hold on to the Crimea area. They made a brief resurgence in the 1st century CE, but were defeated by the Roman empire and the Sarmatians around 200 CE. Before long, the Scythians were absorbed by the Sarmatians. Below is a Latin map of the Roman empire around 125 CE (most of the time we learn about the nomads through books and maps of sedentary societies such as the Romans). It shows the Sarmatae (Latin for Sarmatians) were occupying the present-day Ukraine areas. The Sarmatians also occupied the steppe area of Central Asia (outside of the Roman map).

The Sarmatians engaged in many battles with its neighbors, including the Roman empire. Some of the battles were against the Roman empire and some in alliance with the Roman empire against other countries. After living in Europe for a long time, they gradually became sedentary. The initially matriarchal character of the Scythian/Sarmatian culture (e.g., women warriors) gradually disappeared as the tribes became more organized, the political power of the generals grew, and new military tactics, armor, weapons, and riding equipment (metal stirrups) were introduced. By the 6th century CE the Sarmatians were assimilated with other European populations.

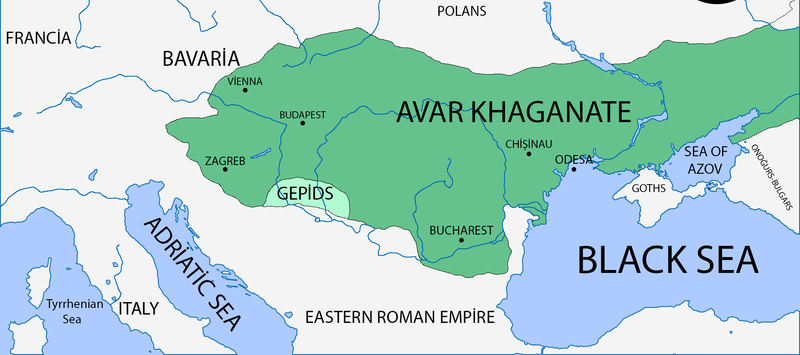

While the Sarmatians were in decline, another tribe from the Steppe, the Avars, moved to the west. The Avars were a confederation of diverse people consisting of various tribes. They formed a Khaganate around 400 CE. By 500 CE they had arrived Europe and fought with some European countries. Around 600 CE the Avars had established a nomadic empire ruling over a multitude of peoples and stretching from modern Austria in the west to Ukraine and then to Kazakhstan in the east. Below is a map of the Avar Khaganate around 600 CE.

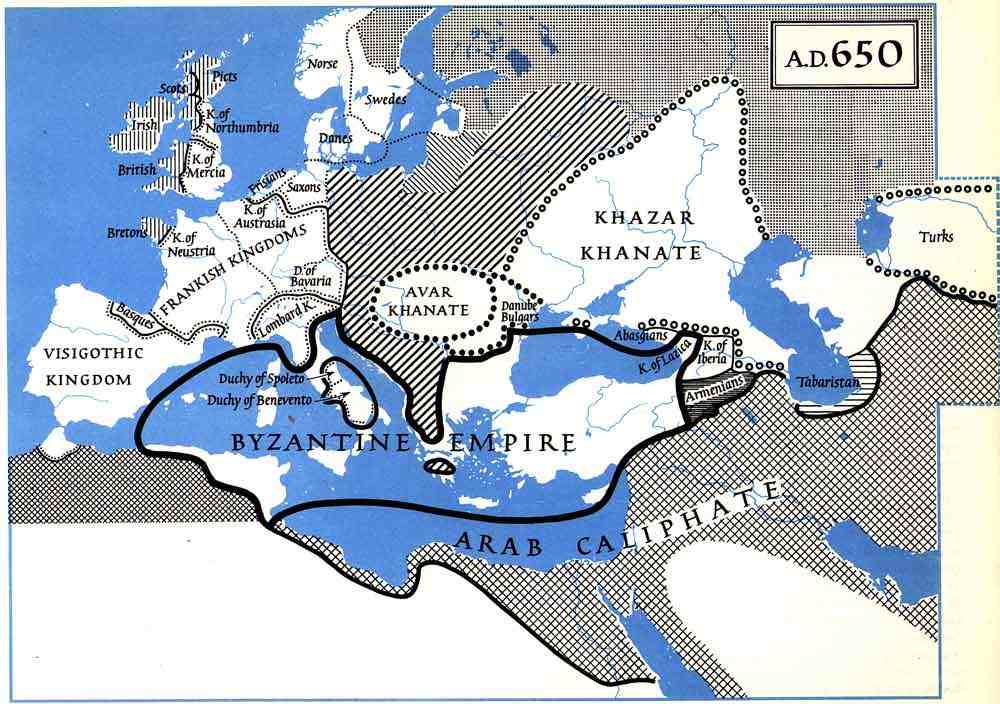

For a time they acted as mercenaries for the Byzantine empire. However, the situation changed and the Avars attempted to invade Italy in 610 and attacked Constantinople in 619 and 626 CE. They were defeated. Below is a map of the Avar Khaganate around 650 CE with greatly diminished territories.

Little is known about the Avars in the next 100 years except that most of their neighbors still called them Avars. In 791 CE they invaded Europe once again. However, they were defeated in 803 CE by Franks led by Charlemagne (747-814 CE), who was the first Holy Roman Emperor. From that time on, they were ruled by the Franks and assimilated with the Europeans.

While the Avars were disappearing, another nomadic group, the Pechenegs (also called Patzinaks) arrived Europe. They were a Turkic ethnic people from Central Asia who spoke a language which belonged to a branch of the Turkic language family. Originally they were part of the Turkic Khaganate in the Steppe. After the Turkic Khaganate collapsed near the end of the 8th century CE, they marched westward and reached the eastern border of Hungary. The Pechenegs invaded the dwelling places of the eastern Hungarians, and expelled them from the lands. By the 9th and 10th centuries, the Pechenegs controlled much of the steppes of southeast Europe and the Crimean Peninsula. Like most nomadic tribes the Pechenegs' concept of statecraft failed to go beyond random attacks on neighbors, which made them mercenaries for other powers. Below is a map showing the Pechenegs around 1000 CE.

In the 9th century, the Byzantines became allied with the Pechenegs, hiring them as mercenaries to fend off other, more dangerous tribes such as Kievan Rus' (an area of mostly Slavic people) and the Hungarians. The Pechenegs began a period of wars against Kievan Rus'. For more than two centuries they had launched raids into the lands of Kievan Rus', which sometimes escalated into full-scale wars. Eventually they were defeated by the Kievan Rus' in 1036 and moved towards the Danube, crossed the river, then disappeared.

By the time the Pechenegs were defeated, a new nomadic group had arrived Europe. This was a tribal confederation in the western part of the Eurasian Steppe, between the 10th and 13th centuries. The group was a confederation dominated by two Turkic nomadic tribes: the Cumans and the Kipchaks. By the 11th and 12th centuries, the nomadic confederacy were the dominant force over the vast territories stretching from the present-day Kazakhstan, southern Russia, Ukraine, to southern Moldavia and eastern Wallachia in present day Romania. Below is a map of the Cuman-Kipchak territories (in red):

The vast territory of this Cuman-Kipchak realm, consisting of loosely connected tribal units who were the military dominating force, was never politically united by a strong central power. Cumania was neither a state nor an empire, but different groups under independent rulers, or khans, who acted on their own initiative, meddling in the political life of the surrounding states: the Russian principalities, Bulgaria, Byzantium and the Wallachian states in the Balkans, Armenia and Georgia in the Caucasus, and Khwarezm. This nomadic group ended its existence in the middle of the 13th century, with the Great Mongol Invasion of Europe. In 1223, Genghis Khan defeated the Cumans-Kipchaks and their Rus' allies at the Battle of Kalka (in modern Ukraine), and the final blow came in 1241, when the Cuman-Kipchak confederacy ceased to exist as a political entity, with the remaining Cumania tribes being dispersed, either absorbed by Mongol conquerors as part of what was to be known as the Golden Horde, or fleeing to the west, to the Byzantine Empire, the Bulgarian Empire, and the Kingdom of Hungary.

Below is a book on the West nomads around the Steppe. The author, Vasily Vladimirovich Bartold (1869 – 1930) was a Russian historian of German descent who specialized in the history of Islam and the Turkic peoples (Turkology). After the Russian Revolution, Bartold was appointed director of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, a post he held from 1918 to 1921. He wrote three authoritative monographs on the history of Islam, namely Islam (1918), Muslim Culture (1918) and The Muslim World (1922). He also contributed to the development of Cyrillic writing for the Muslim countries of Central Asia.

Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion (file size: about 16 MB)

Below are one book and two papers about the Scythians:

(1) The Scythians (file size: about 23 MB)

(3) Once Again “The Scythian” Myth of Origins

(4) Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads

Below are four papers related to the Avars:

(3) The Avar Invasion of Corinth

(4) The genetic origin of Huns, Avars, and conquering Hungarians

Below is a paper related to Cuman Kipchack:

Turkic Ethnic Realities in the Medieval Manuscript of Kipchak Origin

Below is an article related to Hungary:

Maternal Genetic Ancestry and Legacy of 10th Century AD Hungarians