Achaemenid Persian Empire

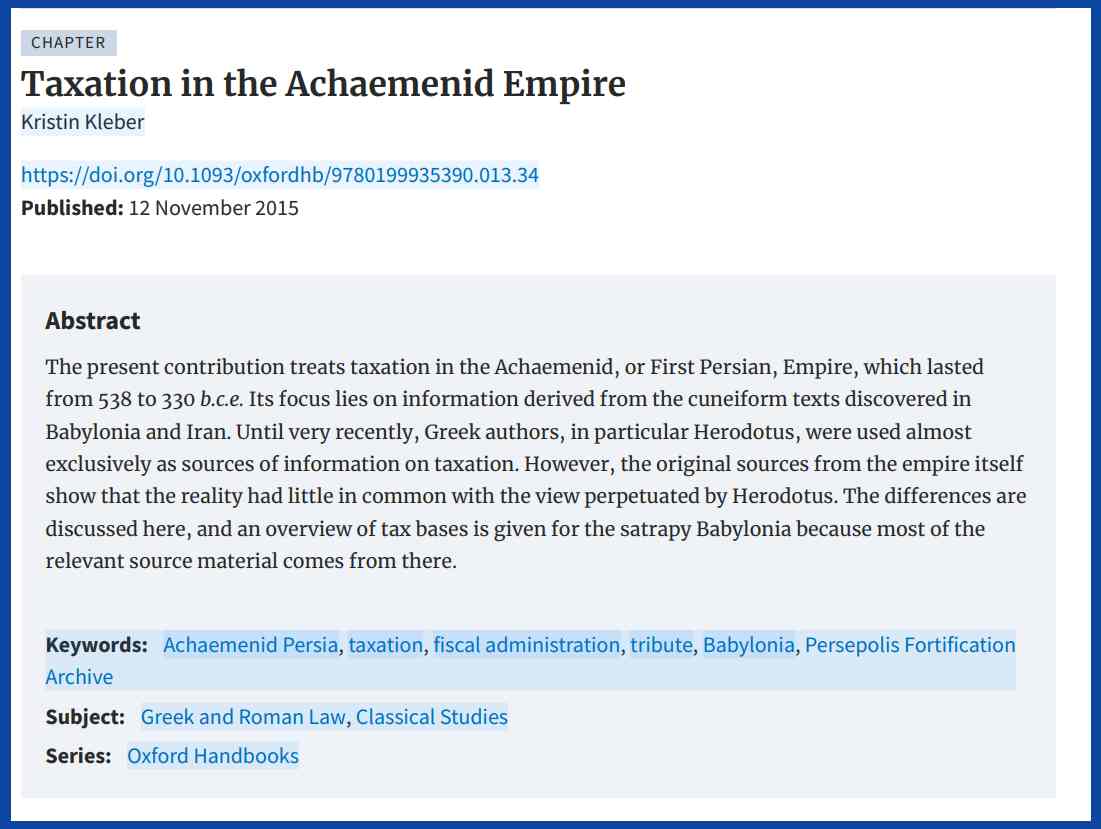

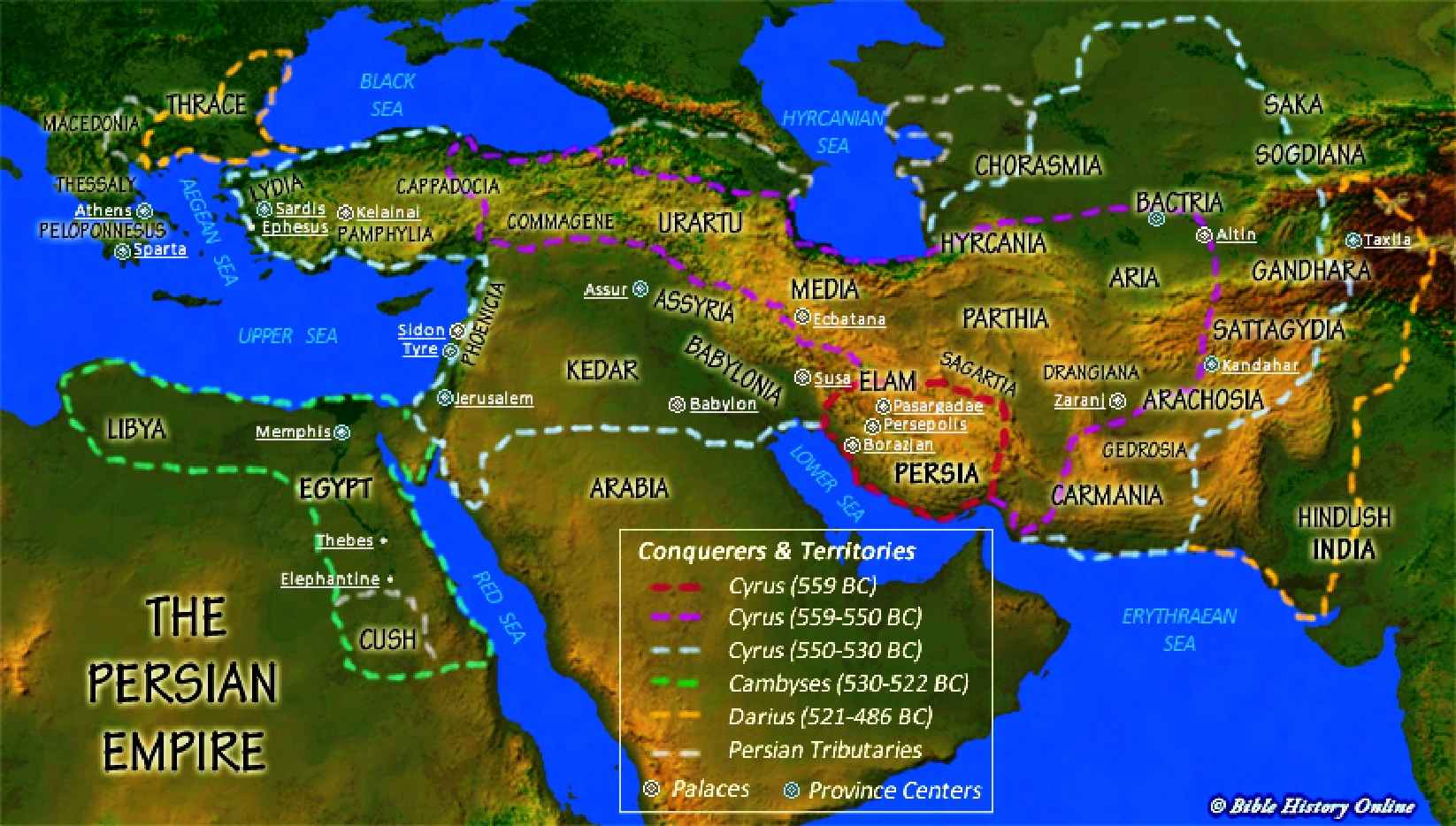

The Achaemenid Persian Empire was the largest that the ancient world had seen up to its time, extending from Anatolia (present-day Turkey) and Egypt, across western Asia, through Central Asia and reached the Indus Valley of India in the east. Its formation began in 550 B.C., when King Astyages of Media, who dominated much of Iran and eastern Anatolia, was defeated by his southern neighbor Cyrus II, king of Persia (reigned 559–530 B.C.). The Achaemenid Empire built spectacular cities, temples and other big structures. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (or Tomb of Mausolus), built around 350 BCE by Mausolus, a satrap (i.e., governor) of the Achaemenid Empire, was listed as one of the seven wonders of ancient world. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by successive earthquakes from the 12th to the 15th century. Below is an interpretation of the Mausoleum by Maarten van Heemskerck (1497-1574), who had drawn pictures of all seven wonders of the ancient world together with the Colosseum in Rome:

Cyrus II was the fifth ruler of a small Persian dynasty started by Achaemenes, reigned between 705-650 BCE. Because of his magnificent achievement, he was also called "Cyrus the Great." Before Cyrus II, the dynasty centered in Persis (located at the southwest portion of present-day Iran) and was a vassal state of the Media. Shortly after he became king, he consolidated other tribes into a federation. Cyrus II then rebelled against Media in 553 BCE. Three years later, he captured the Median king and conquered Media's capital city, Ecbatana.

Cyrus II took the title "Shah ('King') of Persia" and built a capital, which he called Pasargadae, after his tribe. Below is a map showing Persis, Media and the location of Ecbatana, Pasargadae and Persepolis (ceremonial capital of the Empire):

Winning the Media over had landed Cyrus with a vague, sprawling empire of countless different peoples. One skill that Cyrus II developed was to tolerate diversity so as to win over his subjects. These people were contented to live under the rule of Cyrus II.

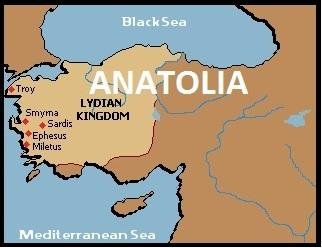

Cyrus II’s army then moved west to Lydia, which is located in part of present-day Turkey. At that time, Lydia was ruled by King Croesus. Once again, Cyrus II won. Lydia was won because Cyrus did not play by the rules. After an indecisive battle near the Halys river one autumn, King Croesus returned to Lydia’s capital Sardis, expecting to resume fighting in the spring according to custom. But Cyrus II followed him home and captured Sardis itself in 546 BCE. Sardis was the richest city in Lydia. Its capture added wealth to Persia. As for Croesus himself, Cyrus II had spared his life, which was unusual at that time because it could be seen as a sign of weakness. Cyrus II developed a reputation for sparing conquered rulers so he could ask their advice on how best to govern their lands. How much of this reputation was warranted is hard to know. Below is a map showing Anatolia, Lydia, Sardis and other major cities:

Cyrus II went on to secure the main prize: Babylon, the capital of the powerful nation Babylonia. Rather than trying to take Mesopotamia's greatest city by force, Cyrus fought a propaganda campaign to exploit the unpopularity of its king, Nabonidus. Cyrus II’s message was that Babylon's traditions would be safer with Cyrus. As a result, Babylonian did not resist him when he marched into the city in 539 BCE.

Once in Babylon, Cyrus II performed the religious ceremonies Nabonidus had neglected and returned confiscated icons to their temples around the country. These acts enabled Cyrus II to claim legitimate rule in Babylon, a rule sanctioned by the Babylonian gods. He then explained how he would rule in his empire -- his would be an empire based, in effect, on a kind of contract between himself and the various peoples in his care. They would pay their tribute, and he would ensure all were free to worship their own gods and live according to their customs.

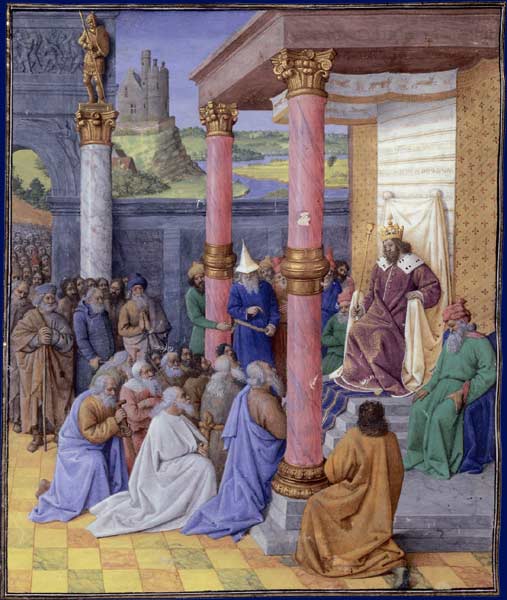

According to the Hebrew Bible, a large number of Jews were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat in the Jewish–Babylonian War and the destruction of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. After the conquer of Babylonia, Cyrus II allowed the exiled Jews to go home in 539–530 BCE and gave them money towards the building of a new temple in Jerusalem. The Jews were thankful and the Hebrew Old Testament recorded Cyrus II in favorable lights. Below is a 1470 painting depicting Cyrus II and the Jews:

Cyrus II turned his attention to Massagetae (located in present-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan). People there wore Scythians dress and follow their mode of living (Scythians are people from the Eurasian Steppe. For details, see the West Nomads page). At that time, Massagetae were ruled by Tomyris, the widowed wife of the king of Massagetae. In order to acquire her realm, Cyrus II first sent an offer of marriage to their ruler, the empress Tomyris, a proposal she rejected. He then commenced his attempt to take Massagetae territory by force. However, he was defeated and killed by Tomyris in 530 BCE. Below is a 1622 CE painting showing the presentation of the head of Cyrus II to Tomyris:

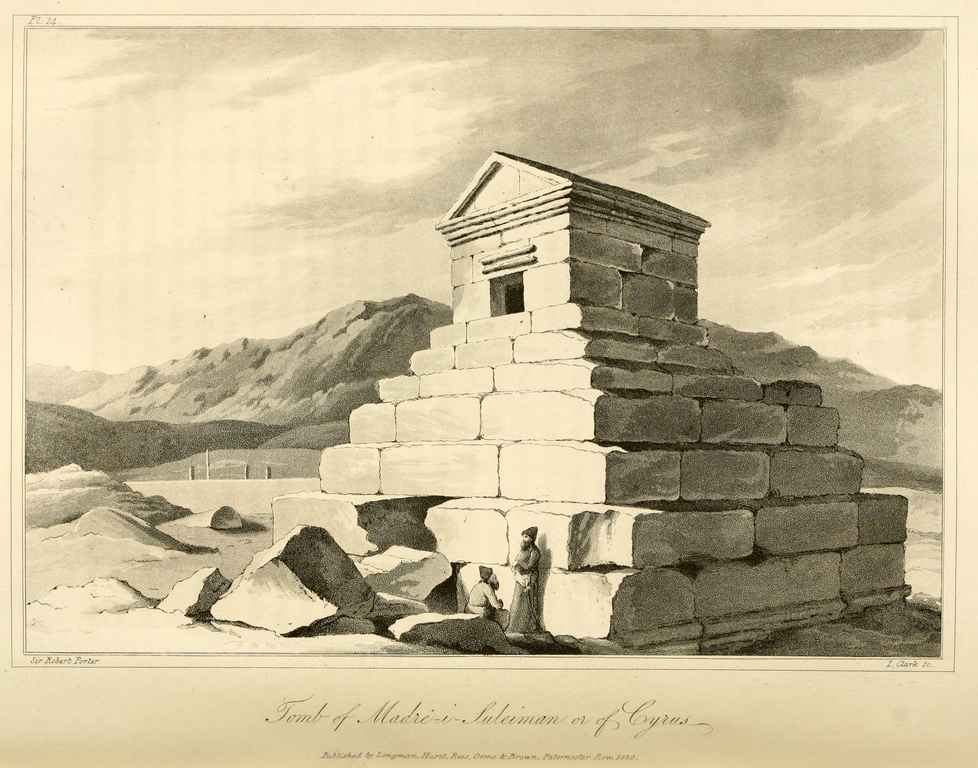

Cyrus II was buried in his capital, Pasagardae. His tomb was massive but very simple. Below is a sketch of the tomb drawn by Robert Ker Porter around 1821:

Below is a modern rendition of the Tomb:

Below is a map showing the boundary of the Achaemenid Empire around the time of the death of Cyrus II.

Cyrus II was succeeded by his son Cambyses. Shortly before Cyrus II departing on his campaign against the Massagetae, Cambyses was appointed the crown prince. When Cyrus II died, Cambyses succeeded him without any trouble. The early years of Cambyses' reign were relatively uneventful.

In 525 BCE Cambyses invaded Egypt. The pretext was that Egyptian Pharaoh Amasis II had broken his promise to marry off his own daughter to Cambyses, instead sending the daughter of another person. Cambyses reached the city of Pelusium, where the easternmost branch of the Nile Delta reaches the Mediterranean Sea. The Persian troops defeated the Egyptians in battles and went on to lay siege to Memphis, a major city. After the fall of Memphis, Cambyses continued to march along the Nile, and by August 525 BCE all of Egypt was in Persian hands. The neighboring Libyan tribes and the Greek city-states along the Libyan coast voluntarily submitted to the rule of Cambyses. Upon his conquest of Egypt, Cambyses went to the Egyptian capital of Sais to have himself crowned pharaoh. He took on an Egyptian throne name and took part in Egyptian ceremonies, like his father Cyrus II had done upon conquering Babylon.

While Cambyses was in Egypt, there was a revolt back home. Cambyses immediately gathered his army and marched back to Persia. However, he died in April 522 BCE while he was on his way home.

Cambyses had no heir. This allowed one of his generals, a distant relative, to step in. His name was Darius. He returned to Persia and put down the revolt. Darius decided to turn his attention to the east. He extended the Achaemenid Empire all the way to the Indus Valley of India.

Darius realized that if the empire were to work, it needed efficient organization. He divided it into 20 satrapies, or provinces, each paying a fixed rate of tribute to Persia. Each satrapy was run by a centrally appointed satrap, or governor, often related to Darius. To prevent the satrap building a power base, Darius appointed a separate military commander answerable only to him. Imperial spies known as the 'king's ears' kept tabs on both and reported back to Darius through the postal service – the empire was connected by a network of roads along which couriers could change horses at stations spaced a day's travel apart. Below is a map showing Darius' territories around 500 BCE and the location of the satrapy.

Darius took much of this structure from the Assyrians, simply applying it on a larger scale, but his use of tribute was something new. Previously, tribute had been essentially protection money paid to avoid trouble, but Darius treated it as tax. He used it to build a navy and embarked on massive public-spending programmes, pumping money into irrigation works, mineral exploration, roads, and a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea.

He also established a common currency, which made working far from home much easier. Darius now brought together teams of craftsmen from all over the Empire to build, under the direction of Persian architects, an imperial capital at Persepolis. Here he could keep his gold and silver in a giant vault and show off the multi-ethnic scope of his empire. Persepolis became a display case for the artistic styles of just about every culture within the empire, held in a frame of Persian design.

Darius considered his achievement bigger than Cyrus II. He dropped the title of Shah and adopted the grander Shahanshah ('King of Kings').

Near the end of Darius’ reign, troubles started to develop in the Mediterranean. There were rebellions in the Greek city-states and Egypt. Darius died in 486 BCE. It fell to Darius's son Xerxes I (486–465 BCE) to restore order in Egypt and the Greek city-states. Although the rebellions were put down, the Achaemenid Empire started to decline.

Below is a map showing the expansion of the territories of the Achaemenid Empire under the kings described above (map copyrighted by Bible History Online, and its website states that the map can be freely distributed):

The Achaemenid Empire was overthrown by Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 BCE, who himself built a big empire.

Religion

Mithra was the most widely worshipped and followed deity in the Achaemenid Empire. Together with the Hindu Vedic mitra, Mithra originated from Proto-Indo-Iranian belief.

His temples and symbols were the most widespread in Achaemenid Empire, most people bore names related to him and most festivals were dedicated to him.

Religious toleration has been described as a "remarkable feature" of the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus II assisted in the restoration of the sacred places of various cities, including Jerusalem.

Zoroastrianism was the state religion. Mithra was mentioned in various texts of Zoroastrianism. Below is a 4th century rock relief of Mithra.

Roads and infrastructure

Under the Achaemenids, trade was encouraged and there was an efficient infrastructure that facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire. Tariffs on trade, along with agriculture and tribute, were major sources of revenue for the empire.

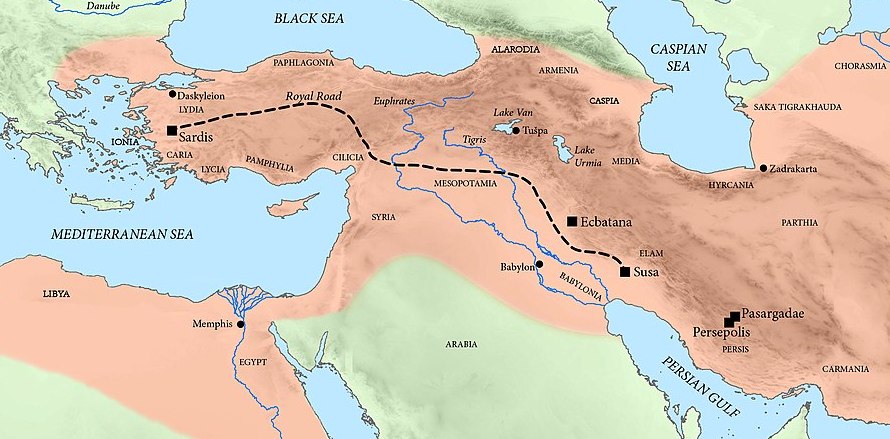

The satrapies set up by Darius were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch being the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis, built by command of Darius. It featured stations and caravanserais at specific intervals. The relays of mounted couriers could reach the remotest of areas in fifteen days. Despite the relative local independence given by the satrapy system, royal inspectors, the "eyes and ears of the king", toured the empire and reported on local conditions.

Another highway of commerce was the Great Khorasan Road, an informal mercantile route that originated in the fertile lowlands of Mesopotamia and snaked through the Zagros highlands, through the Iranian plateau and Afghanistan into the Central Asian regions of Samarkand, Merv and Ferghana. Following Alexander's conquests, this highway allowed for the spread of cultural syncretic fusions like Greco-Buddhism into Central Asia and China, as well as empires like the Kushan, Indo-Greek and Parthian to profit from trade between East and West. This route was greatly rehabilitated and formalized during the Abbasid Caliphate, during which it developed into a major component of the famed Silk Road.

Below is a map showing the Royal Road:

Below are books and articles on the Achaemenid Empire:

(1) History of the Persian Empire (file size approximately 24 MB)

(2) Art of the Achaemenid Empire, and Art in the Achaemenid Empire

(3) Taxation in the Achaemenid Empire