Kucha

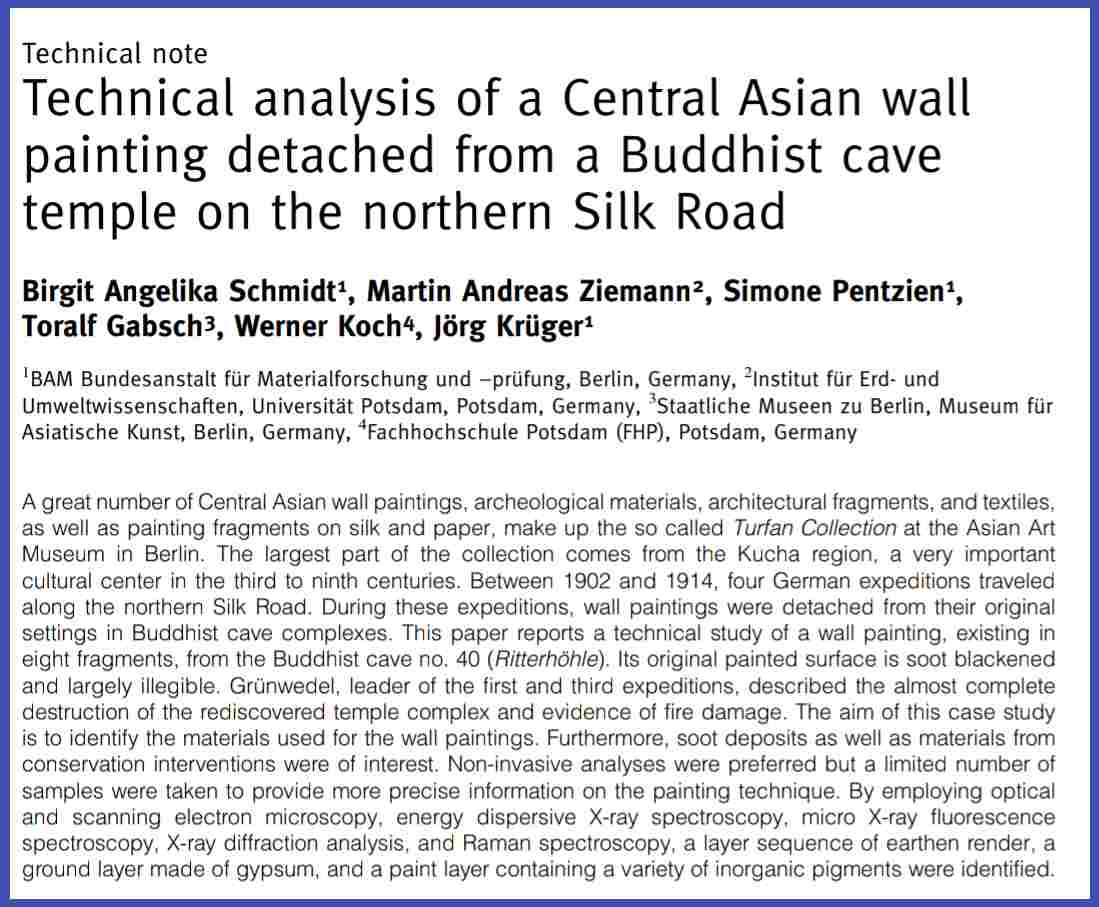

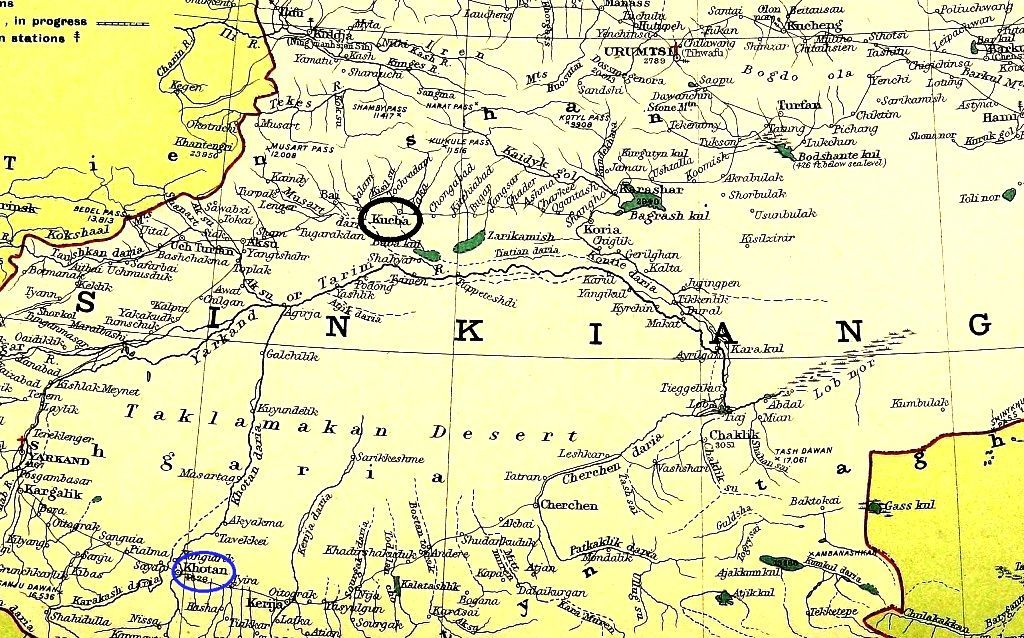

Kucha is an oasis located at the northern edge of the Taklamakan desert in the Tarim Basin. The oasis was supported by several tributaries of the big Tarim river, especially the Kucha and Muzart rivers. Below is a 1900 CE map with Kucha circled in black. It shows the Tarim river and its many tributaries. At the lower left corner of the map is Khotan, an oasis at the southern edge of the Taklamakan desert, circled in blue. Also included is a map of Asia showing roughly the location of the above map in a black box:

For a long time Kucha was the most populous oasis in the Tarim Basin. It was on the northern Silk Road and had contacts with China, India, and Central Asia countries. In the second century CE a Roman traveler, Maes Titianus, visited it. Because of its location, Kucha was on the route of many conflicts between major powers around the region. It was under the rule of China, Xiong-nu, Tibet, Uyghur and Mongol at different times, with periods of semi-independent. Below is a painting of a Kucha ambassador sent to China around 520 CE. The painting contains Chinese explanatory text on the diplomatic mission.

This large city on a busy trade route was a natural place for many Indian monks to rest when they were on their way to China. Some took up residence in the city. By third century CE Kucha became a major center of Buddhism. At first, it was a center for Sarvastivada, one of the 18 schools of Buddhism. Eventually it became a center of Mahayana Buddhism. In this respect it differed from Khotan, a kingdom on the southern side of the desert that was dominated by Mahayana from the start. The most influential monk in Kucha is Kumarajiva. Later in his life he lived in China and was responsible for the translation of many Sanskrit Buddhist texts into Chinese, some of those translations are still being recited by Chinese Buddhists today.

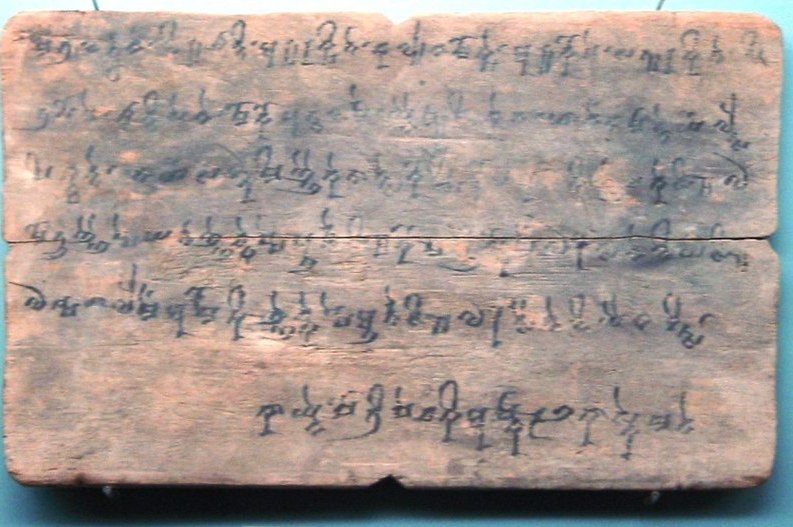

Another reason for Kucha to be a prominent Buddhist city is that its native language, Kuchean, also known as Tocharian B and is now extinct, belongs to the same Indo-European language class as Sanskrit used in India. Thus it was easy to translate Buddhist documents to Kuchean. Below is a picture of a wooden plate with an inscription in Tocharian B.

Near Kucha is collection of caves called the Kizil Caves. It was one of the earliest major Buddhist cave complex in China. There are almost 236 caves carved into the cliff which stretch from east to west for a length of 2 km. Using radioactive carbons dating, some of the caves were dated to around 3rd century CE. It was also believed that the caves were abandoned around the beginning of the 8th century. Below is a picture of a section of the Kizil mountain with caves.

The art of the Kizil caves showed Indian and Persian (Iranian) influence. For instance, the murals of some caves show a clear Persian influence during the Sasanian period, as reflected in the painting below. It shows two Sasanian ducks with jeweled necklaces in their beaks which were drawn facing one-another within pearl-shaped medallions. Many such works created in the Indian or Persian style were to be found among the Buddhist art of the caves.

The Sasanian Empire (226-651 CE), whose artistic conventions so influenced the murals, ruled a vast area covering the Iranian Plateau and Mesopotamia; and at its peak, extended its rule as far as Afghanistan. At that time Afghanistan was a Buddhist country. It was possible that Buddhist monks from this region traveled east along the Silk Road and applied Sasanian and Indian art techniques to the caves.

Below is relief from a Kizil cave showing Brahmana Drone and several Indian kings. Brahmana Drone is an important figure in Indian epic. This relief shows Indian influence.

Chinese influence on the caves started to show from around the sixth century CE and intensified during the 7th century when the Tang dynasty controlled the Tarim Basin. In 753 CE, the northern part of the Tarim Basin was taken over by the Turks of the Uyghur Khaganate. Tibetan also controlled the area in 790 CE. By 900 CE, the area was under Muslim domination. The caves had already been abandoned at that time.

Three recent papers are provided:

(3) Buddhist Narrative Depictions in Andhra, Gandhara and Kucha – Similarities and Differences that Favour a Theory about a Lost “Gandharan School of Paintings” (published 2013 in Buddhism and Art in Gandhara and Kucha)