Inca Empire and Civilization

The Inca empire was the last and largest empire in South America before the Spanish invasion. Its territories consisted of present day Peru, western Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, a large portion of Chile, and the southwest-most tip of Colombia. Thus it is useful to study the empire and its civilization to help us understand the culture of many countries in South America. Below is a map of the Inca empire with the expansion timetable:

There is another reason to study it. Most people are familiar with civilizations in Asia and Europe. Was the Inca civilization similar? There is at least one major difference that warrants a close look.

Starting from the second half of 18th century some European thinkers advocated socialism. Examples are Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825), Charles Fourier (1772-1837) and Robert Owen (1771-1858). In 1848 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the Communist Manifesto (see section F of the notable events in history page), and they discussed socialism extensively in part one of the Manifesto. The ideas of all these people came to fruition when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was formed in 1922. From its formation to collapse in 1991, the USSR was ruled by the Communist Party and implemented socialism principles.

Yet far away from Europe and unbeknown to these Europeans, a large socialist country had already exited. This country is the Inca empire (1438-1533 CE). A French economist, Louis Baudin (1887-1964), studied this country and published a book titled “A Socialist Empire: The Incas of Peru”. The Incas did not use money and had no trading class in the economy. The production, distribution, and use of commodities were centrally controlled by the Inca government. Each citizen of the empire was issued the necessities of life out of the state storehouses, including food, tools, raw materials, and clothing. Basically, the citizens needed to purchase nothing. As a result, the country had no need to issue currency to facilitate trading. The Inca empire was very different from other large empires in Europe and Asia.

The Inca empire has other unique characteristics. It did not have a written language, yet the regime was able to govern a large area with diverse population. It did not use wheels to carry materials, and instead, used pack animals (especially llama, which is a domesticated South American animal) to transport materials by attaching them so the weight bears on the animal’s back. Below is a picture of an aboriginal girl and her llama:

The Incas did not use animals to aid in physical labor (e.g., oxen for farming). It did not use iron and used only bronze (other civilizations at similar time used both). Yet the Incas built more than 18,600 miles/30,000 km of paved roads in the most rugged terrain in the world (a large part of its territories was on the Andes Mountains, the longest continental mountain range in the world). As a comparison, the circumference of the earth at the equator is 25,000 miles/40,000 km. Thus the length of the Inca roads were equal to three quarters of earth's circumference. These roads and all infrastructure along them are protected by UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1994. Below is a picture of an Inca built road that still exists today:

The Incas also developed impressive architecture, which is widely admired for its fine masonry. One example is huge stonewalls that feature precisely cut and shaped stones closely fitted together without using mortar (or other adhesives) to bind them. Yet these stonewalls were able to withstand the impact of strong earthquakes, which occurred frequently because a large part of the Inca empire sit on the Andean volcanic belt along the “ring of fire.” Below are a map of the ring of fire and a picture of stonewall of Coricancha (the Golder Temple) built by the Incas (located in Cusco, Peru):

The original Inca people began as a tribe in the Cuzco, Peru, area around the twelfth century CE. It is believed that there were about 15,000 to 40,000 of them. Under the leadership of Manco Capac, they formed the small city-state of Kingdom of Cuzco around 1200 CE. In 1438 CE, under the command of Sapa Inca (paramount leader) Pachacuti (reign: 1438–1471), they began their expansion into the Andean regions of South America and adjacent lands. Through arm conquest, diplomacy, and peaceful assimilation, the land they ruled was many times the size of their original city-state and had a population of about 10 million. The Inca Empire lasted about 100 years. Through ingenuity, hard work, and excellent organization, the Inca managed to build an empire with impressive social, cultural, and material achievements. The empire ended after the arrival of Spanish invaders with advanced technology. The Spanish invaders also brought with them viruses (e.g., smallpox and measles) to which people in South America had no natural immunity, causing apocalyptic plagues to the people of Inca. Whether the Inca economic system would continue to prosper or collapse (similar to the collapse of the USSR economy) without the Spanish invasion remains unknowable. But it is fascinating to study the Inca society as it was. Let us get a more detailed look at the Inca society.

The Incas had a centrally planned economy, perhaps the most successful ever seen. Its success was in the efficient management of labor and the administration of resources they collected as tribute. Collective labor was the base for economic productivity and for the creation of social wealth in the Inca society. Every citizen was required to contribute with his labor and refusal or laziness was punishable (with the death penalty in severe situations). Labor was divided according to region: agriculture would be centralized in the most productive regions, similar for ceramic production, road building, textile and other skills. The government collected all the surplus after local needs were met and distributed it where it was needed. In exchange for their work citizens had free clothing, food, health care and education. Their economy was so efficiently planned that every citizen had their basic needs met.

The Inca community -- Ayllu:

The “ayllu” was at the center of the Inca Empire economic success. Ayllus were composed of families that lived near each other in the same village or settlement. Ayllus also provided social cohesion as people who were born in one ayllu also married within the ayllu. Each ayllu specialized in the production of certain products depending on its location. Agricultural ayllus were located close to fertile land and produced crops that would be optimized for the type of soil. Their output would be given to the government which in turn would redistribute it to other locations where the product was not available. Surplus would be kept in “qullqas,” which are storage houses along roads and near population centers. Qullqas were generally built outside the towns, and were mostly built on the sides of hills that were high and well ventilated. The breeze and wind served to naturally keep temperatures down and preserve the food. The storage buildings had channels for ventilation and systems of drainage. The channels were generally under the qullqa floors to direct humidity away and it was possible to control the humidity of the earth in the storage units. This helped preserve foods that required dryness to avoid rot. Below are picture of: (1) a qullqas complex above Ollantaytambo, Peru, and (2) the remains of a qullqa in the Mantaro Valley, Peru:

Other ayllus would specialize in producing pottery, clothing or jewelry. Skills were transferred from generation to generation within the same ayllu. These ayllus produced all the products necessary for everyday living, and the Incas developed extensive network of roads that allowed distribution of products to various ayllus (see Inca Road System section below). The abundance and diversity of resources and its availability during bad years and war made the population loyal to the local government and to the paramount ruler (Sapa Inca).

The use of the land was a right that individuals had as members of the ayllu. The head of the ayllu (called curaca) redistributed the land to each member according to the size of their families. The dimensions of the land varied according to its agricultural quality and it was measured in tupus, a local measurement unit. A married couple would get one and a half tupus, for each male child the couple received one tupu and for each female half a tupu. When the son or daughter started their own family, a tupu was taken away and given to the new family. Each family worked their land but they did not own it -- the Inca estate was the rightful owner.

Collective labor and taxes:

There were three ways in which collective labor was organized.

The first one was the "ayni" to help a member of the community who was in need. Example: build a house for the weak or help a sick member of the community.

The second was the "minka" or team work for the benefit of the whole community. Examples of minka are building agricultural terraces and cleaning the irrigation canals.

The third one was the "mita" or the tax paid to the government. Since there was no currency, taxes were paid with crops, cattle, textile and specially with work. Mita laborers served as soldiers, farmers, messengers, road builders, or whatever needed to be done. It was a rotational and temporary service that each member of the ayllu was required to meet. They built temples and palaces, canals for irrigation, agricultural terraces, roads, bridges and tunnels, etc. This system was a balanced system of give and take. In exchange the government would provide food, clothing and medication. This system allowed the empire to have all the necessary produce available for redistribution according to necessity and local interests.

By working together people in the empire created such wealth that the Spanish were astonished with what they encountered.

Inca Accounting System -- Quipus:

The Incas and their predecessor did not develop a writing system. However, they created the "quipu" to keep track of transactions. The Quipu consists of fringes of color strings attached to a horizontal string and made of cotton or llama wool. The hanging strings would contain knots which carried a meaning. There were different types of knots such as the single, figure eight and the four turn long knot. The position in which the knots were tied, the sequence of the knots and the color of the string had a particular meaning. The largest quipu has 1,500 strings.

The Incas used the quipu as an accounting system to record taxes, keep track of livestock, measure parcels of land, recording census, as a calendar, keep track of weather and many other uses. Below are: (1) picture of a quipu, and (2) sketch of a "quipucamayoc" (accountant) from "The First New Chronicle and Good Government", a chronicle of Inca history by the indigenous Inca historian Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala (ca. 1535–1616):

Shown on the lower left side of the sketch is a yupana. A yupana is an abacus-type mechanism used by the Incas to perform arithmetic operations.

Inca Road System:

The Incas were magnificent engineers. They built an elaborate network of roads and bridges. The success of its empire was partly due to being able to reach and control each corner of their territory. There were two main roads, one connected the territory north to south extending along the coast and another along the Andes Mountains. Both roads were connected by a shorter network of roads. Along the coast they built a 3,000 m/4,830 km road that connected the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador in the north to the Maule River, Chile in the south. The Andean royal road constructed in the highlands extended along the Andes Mountains. It reached Quito, Ecuador in the north, passed through Cajamarca and Cusco and ended near Tucuman, Argentina. The Andean Royal road was over 3,500 miles long, longer than the longest Roman road. Below is a map showing the road system:

The Incas did not know the wheel and did not have horses either. Most of the transportation was done by foot using llamas to carry goods from one part of the empire to another. Roads were also used by messengers (called chasquis in Inca) to carry messages across the empire.

The Incas developed techniques to overcome the difficult territory of the Andes. Many roads crossed high mountains. On steep slopes they built stone steps resembling giant flights of stairs. In desert areas they built low walls to keep the sand from drifting over the road.

Suspension Bridges:

Bridges were built all across the empire. They connected roads across rivers and deep canyons on one of the most difficult terrains in the world. These bridges were necessary in the organization and economy of the empire.

The Incas built spectacular suspension bridges or rope bridges using natural fibers. These fibers were woven together creating a rope as long as the desired length of the bridge. Three of these ropes were woven together creating a thicker and longer rope; they would continue braiding the ropes until they had reached the desired width, length and strength. The ropes were then tied together with branches of trees. Pieces of wood were added to the floor creating a cable floor of at least four to five feet wide. The finished cable floor was then attached to abutments supporting the ends on each side. They also attached ropes on both sides of the bridge that served as handrails. The last existing Inca suspension bridge is located near Cusco in the town of Huinchiri. Located on either side of a gorge high in the Peruvian Andes, this aging rope bridge sags precariously over the Apurímac River. It is 28 meters in length, and built 30 meters above the river. The bridge connects three communities: (a) Chaupibanda and Chocayhua communities, which live on the left bank, to (b) the Qollana Quehue community on the right bank. It is the last remaining bridge made of grass fibers in Peru. For the locals, this is a symbol that links its inhabitants with nature and their traditions with their history. Below is a picture of the bridge:

Inca Messengers -- Chasquis:

Because the Inca Empire controlled such a vast territory they needed a way to communicate with all the corners. They set up a network of messengers by which important messages would be conveyed. These messengers were known as "chasquis" and were chosen from the strongest and fittest male youngsters. They ran many miles a day to relay messages. They lived in cabins or tambos along the roads usually in groups of four or six. When a chasqui was spotted, another one would run to meet him. He would run beside the incoming messenger trying to listen and to memorize the message. He would also relay the quipu if there was one. The tired chasqui would stay and rest in the cabin while the other one will run to the next relay station. In this way messages could travel over 100 miles a day.

Below is a drawing of a chasqui holding a quipu:

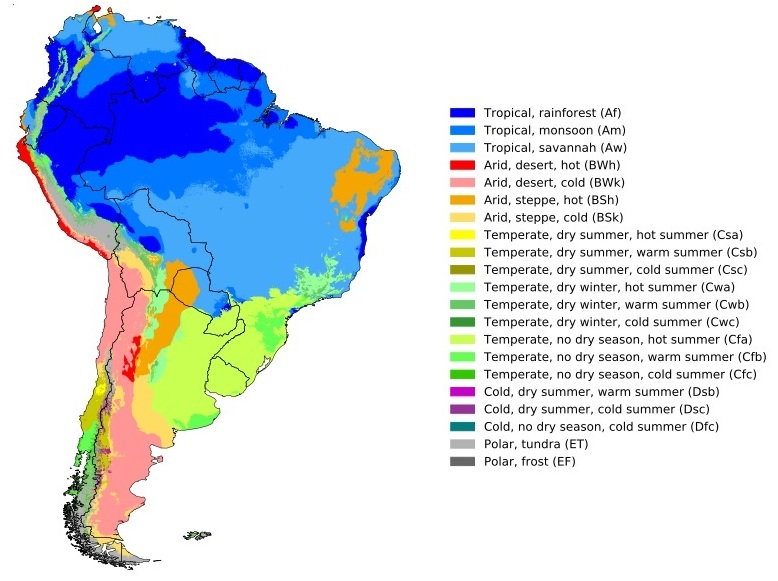

One seldom mentioned aspect of Inca civilization is Inca mummies while Egyptian mummies are known all over the world. Inca mummies arose from ancestor worship and ritual human sacrifice. Some of the mummies were buried with valuable materials such as precious metal jewelry, fine pottery, and sumptuous textiles. The freezing temperature at high mountains (many are over 21,000 ft, or 6,500 meters) and large areas of dry desert environment (for example, the 105,000 square km Atacama Desert in Peru and Chile is considered the world’s driest non-polar location) helped to preserve the mummies. Below are maps of South America showing (1) the altitude and (2) arid areas (which are mainly along the west coast):

Below are publications related to Inca:

(1) A Socialist Empire: The Incas of Peru (file size: about 11 MB)

(2) Inca culture at the time of the Spanish conquest

(3) Putting the rise of the Inca Empire within a climatic and land management context

(4) Women of the Incan Empire: Before and After the Conquest of Peru