Dunhuang

Dunhuang is an oasis city on the Silk Road. Two special attractions of the city are the Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan (or Singing-Sand Mountain, named after the sound of the wind whipping off sand dunes). Below are pictures of (1) Crescent Lake and (2) sand dunes:

Dunhuang is now a popular tourist location. Below is a picture showing tourists on camels walking on the sand dunes:

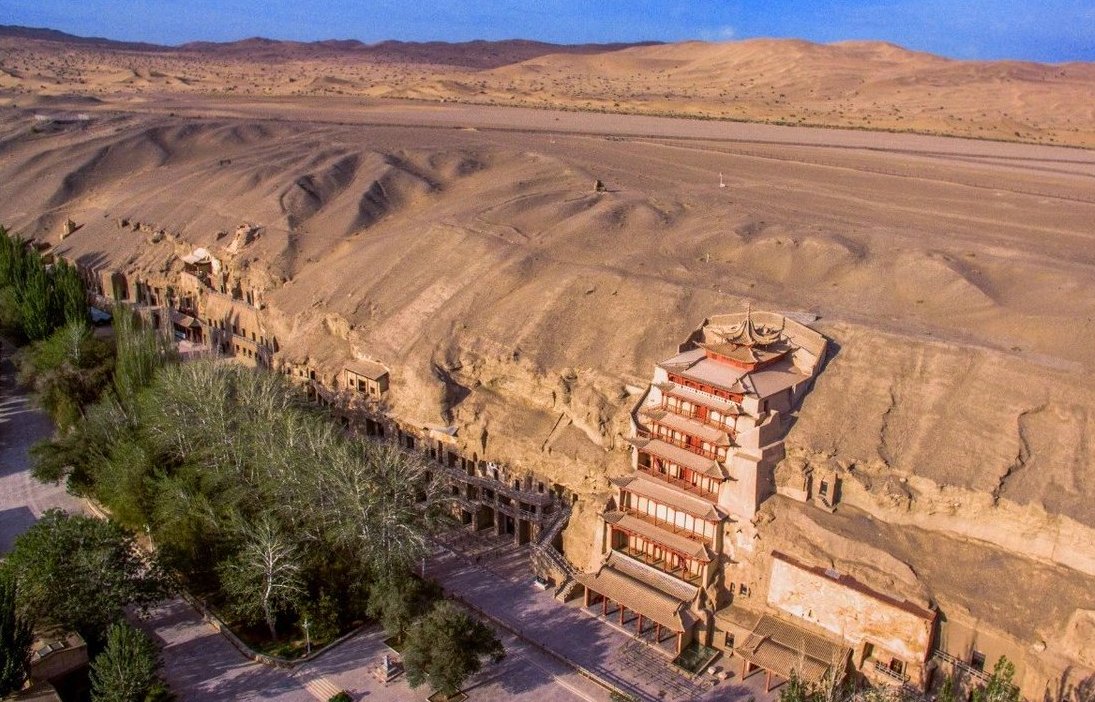

About 25 km away is the world-famous Mogao Caves, which contains hundreds of caves with wall paintings and tens of thousands of valuable ancient documents.

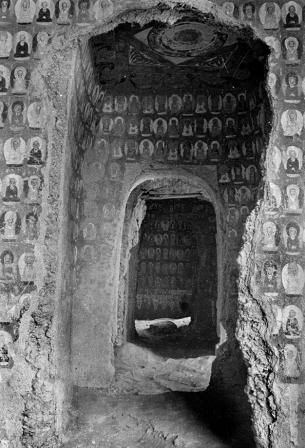

Below are pictures of (1) caves along the hillside, (2) caves at a different hillside showing people exploring the caves, photo taken in 1943 when there were almost no tourists, (3) aerial view showing the tallest cave temple, and (4) entrance to a cave:

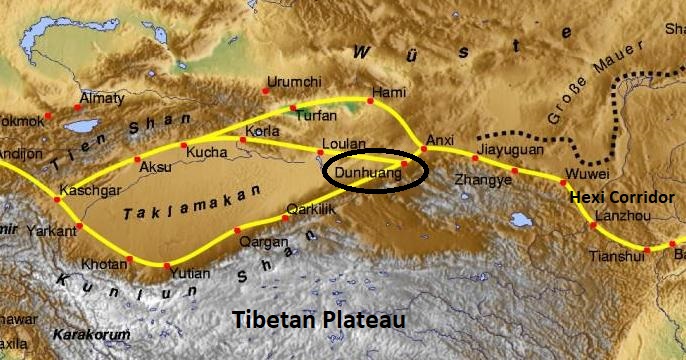

Dunhuang commands a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient south and center Silk Road routes. It also controls the entrance to the Hexi Corridor, which leads straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capital of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an). Below is a map of with Dunhuang circled.

As a frontier town, Dunhuang was fought over and occupied at various times by many people. It was ruled by Chinese dynasties and various nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu during Northern Liang and the Turkic Tuoba during Northern Wei. The Tibetans occupied Dunhuang around 780 CE when the Tang Empire became weakened considerably after the An Lushan Rebellion. Around 848 CE it returned to Tang and ruled by a local general Zhang Yichao. After the fall of Tang, Zhang's family formed the Kingdom of Golden Mountain in 910, but it later came under the influence of the Uighurs. The Zhangs were succeeded by the Cao family, who formed alliances with the Uighurs and the Kingdom of Khotan. During the Song dynasty (960-1279), Dunhuang fell outside the Chinese rule. From the rule by general Zhang Yichao around 848 to about 1036, Dunhuang was a multicultural town that contained one of the largest ethnic Sogdian communities in China. The Sogdians there were sinified to some extent and were bilingual in Chinese and Sogdian, and wrote their documents in Chinese characters, but horizontally from left to right instead of right to left in vertical lines, as Chinese was normally written at the time.

In 1036 the Tanguts, who founded the Great Xia dynasty, captured Dunhuang. Dunhuang was conquered in 1227 by the Mongols, who sacked and destroyed the town. It was rebuilt and became part of the Mongol Empire. Dunhuang went into a steep decline after the Chinese trade with the outside world became dominated by southern sea-routes, and the Silk Road was officially abandoned soon after the Ming dynasty took over China around 1368.

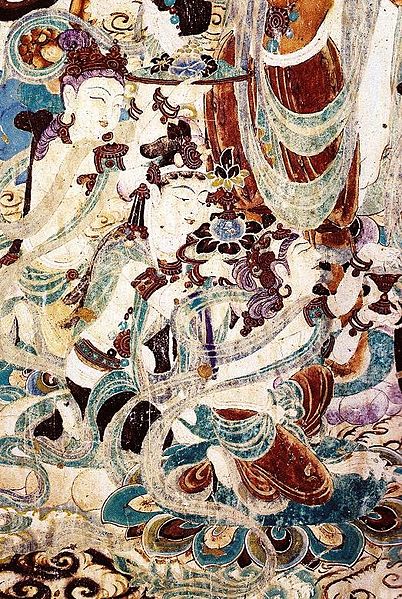

For the next few hundred years Dunhuang was forgotten until archaeologists around 1900 CE discovered the Mogao Caves. The Mogao Caves, also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes or Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, form a system of hundreds of caves with wall paintings and sculptures. Below are some examples of the wall paintings.

Below are some examples of the sculptures found in the caves:

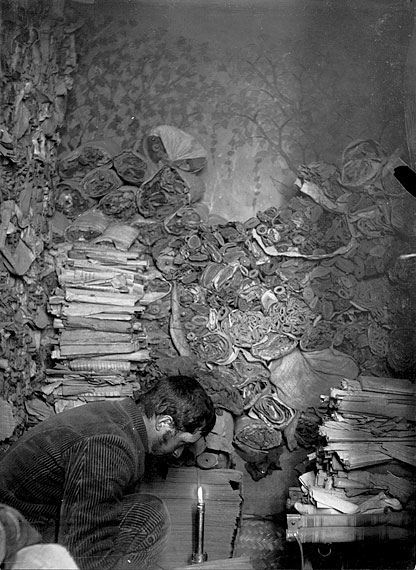

An important cache of documents was discovered in the so-called "Library Cave", which had been walled-up by Dunhuang residents in the 11th century. Many documents were heaped up in closely packed layers of bundles of scrolls. A large number of documents dating from 406 to 1002 were found in the cave. Up to 50,000 manuscripts may have been kept there, one of the greatest treasure troves of ancient documents found. While most of them are in Chinese, a large number of documents are in various other languages such as Tibetan, Uighur, Sanskrit, and Sogdian, including the then little-known Khotanese. The subject matter of the great majority of the scrolls is Buddhist in nature, but it also covers a diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works are original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. Below is a photo of the scrolls in one of the caves.

Many of the manuscripts were previously unknown or thought lost, and the manuscripts provide a unique insight into the religious and secular matters of northern China as well as other Central Asian kingdoms from the early periods up to the Tang and early Song Dynasty. The manuscripts found in the Library Cave include the earliest dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra from 868, which was first translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the fourth century. These scrolls also include manuscripts that ranged from the Christian Jingjiao Documents to the Dunhuang Go Manual and ancient music scores. These scrolls chronicle the development of Buddhism in China, record the political and cultural life of the time, and provide documentation of mundane secular matters that gives a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people of these eras.

Below is a book written by the explorer and archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein related to his expeditions leading to the discovery of the Mogao Caves. Here is the description of him from Wikipedia (assessed 2021)

"Sir Marc Aurel Stein, KCIE, FRAS, FBA (Hungarian: Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at Indian universities.

Stein was also an ethnographer, geographer, linguist and surveyor. His collection of books and manuscripts bought from Dunhuang caves is important for the study of the history of Central Asia and the art and literature of Buddhism. He wrote several volumes on his expeditions and discoveries which include Ancient Khotan, Serindia and Innermost Asia."

Ruins of Desert Cathay Vol. 1 (file size: about 16 MB)

Ruins of Desert Cathay Vol. 2 (file size: about 15 MB)