Khotan

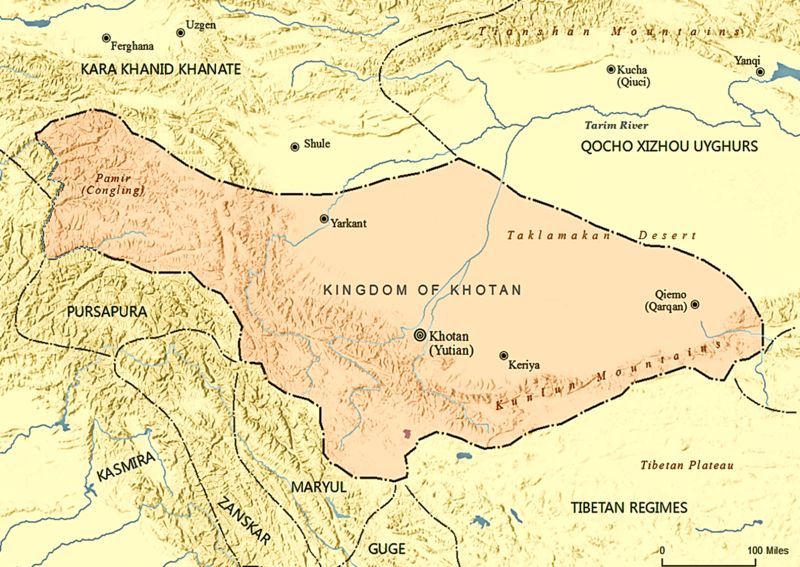

The oasis of Khotan is located on the southern branch of the famous Silk Road, which is the main caravan route connecting China and western Eurasia. The oasis is at the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin and lies just north of the Kunlun Mountains (also known as the Kunlun Shan). It has an elevation of about 4,000 ft.

The oasis has abundance of water because it is served by two rivers: the Karakax (Black Jade) River and the Yurungkax (White Jade) River. (These rivers are also translated as Karakash and Yurungkash). They are fed by the spring snow melt from the Kunlun glaciers. This guaranteed annual water supply allows irrigation for agriculture.

In year 56 CE a kingdom was found – the Kingdom of Khotan. It ended in 1006 CE after being conquered by Kara-Khanid. Around a century later trade on the Silk Road as a whole declined. As people moved out of Khotan and its importance decreased, its history became obscure and slowly forgotten. Below are a map of the Kingdom and a map of Asia showing roughly the location of the first map in a black box:

The discovery of ancient Khotan is due mainly to two famous explorers, the Swedish geographer Sven Hedin and the British-Hungarian archeologist Aurel Stein, who, in 1896 and 1910, explored and described in detail the agrarian settlements and buried cities spread out along the abandoned riverbeds of the southern Taklamakan desert. In addition to the archeological evidence, its past can be patched together from historical sources, mainly the Han and Tang Chinese chronicles. Another source of information was the biographies of Chinese monks who went to India to learn Buddhism and returned to China. Often they included description of countries they visited during their journeys. The most famous monks are Faxian and Xuanzang.

From an early period, the oasis had been inhabited by different groups of people. Surviving documents from Khotan of later centuries indicate that the people of Khotan spoke the Saka language, an Eastern Iranian language. They also spoke Gandhari Prakrit, an Indo-Aryan language related to Sanskrit. Below is a 9th century document written in Khotanese Saka listing the animals of the Chinese zodiac.

There is debate as to how many Khotan's original inhabitants were ethnically and anthropologically South Asian and speakers of the Gāndhārī language versus the Saka, an Indo-European people of Iranian branch from the Eurasian Steppe. In ancient Chinese records the Saka people were known as the Sai (塞) . They originally lived in the valleys of present-day Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Later the Saka would also move into Northern India, as well as other Tarim Basin sites like Khotan, Karasahr, Yarkand and Kucha. Below is a map of present-day Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan:

Below is a 7th century CE drawing showing a man from Khotan:

Chinese also exerted important influence on the inhabitants. Minted coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century CE bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit in the Kharosthi script, showing links of Khotan to India and China in that period. The Saka document above listing Chinese zodiac shows the influence of Chinese culture on Khotanese. Below is a 10th century portrait of a Khotan king found in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. At the left is his title written in Chinese characters.

Thus, for at least a thousand years, from time earlier than the first century CE and into the 11th century, the multicultural kingdom of Khotan, which was Buddhist in religion until the Muslim conquest around 1000 CE, was a center for the exchange and transmission of people and goods, as well as languages, religions, and art, which show Persian, Indian, Greek, Tokharian, and Chinese influence.

Khotan was on the path of the transmission of Buddhism to China. One of the earliest Mahayana scriptures translated from Sanskrit into Chinese, the Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra in 25,000 verses, was brought from Khotan in 282 CE. Since then, other translations were made from the Sanskrit texts brought from Khotan, made by Khotanese monks, or both. One of the monks is Dharmakṣema, who translated the Suvarṇabhāsa-sūtra. After the Muslim conquest of the 11th century people in Khotan slowly converted to Islam.

The economic prosperity of that period can be explained by urban and commercial development made possible by organized irrigation. Khotan is thought to be the first place outside China to cultivate the mulberry to produce and, from the 5th century CE, export silk and silk rugs, making it a center for silk production in the Tarim Basin. Khotan was also famous for its nephrite jade, extracted from the mountains and alluvial deposits from the rivers, such as the Yurungkax River, also called the White Jade River. This made it the starting point of the “Jade Road” which spread this semi-precious stone into the whole of China.

After the Muslim conquest in the 11th century and the eventual abandonment of the Silk Road in the 14th century, economic activity in the Khotan oasis declined. The area of the oasis itself has steadily contracted over time, as is shown by comparison of the archeological data from excavations of cities, agrarian settlements, and remains of orchards in the region. This trend is viewed as a continuation of thousands of years of desertification that is due both to natural factors (such as climate change, especially in hydrology) and to human pressures on marginal lands through practices such as overgrazing.

Aurel Stein wrote two books about Khotan. Both are provided below. Here is the description of him from Wikipedia (assessed 2021)

"Sir Marc Aurel Stein, KCIE, FRAS, FBA (Hungarian: Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at Indian universities.

Stein was also an ethnographer, geographer, linguist and surveyor. His collection of books and manuscripts bought from Dunhuang caves is important for the study of the history of Central Asia and the art and literature of Buddhism. He wrote several volumes on his expeditions and discoveries which include Ancient Khotan, Serindia and Innermost Asia."

Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan (file size: about 11 MB)

Ancient Khotan Vol. 1 (mainly text; file size: about 26 MB)

Ancient Khotan Vol. 2 (mainly plates)